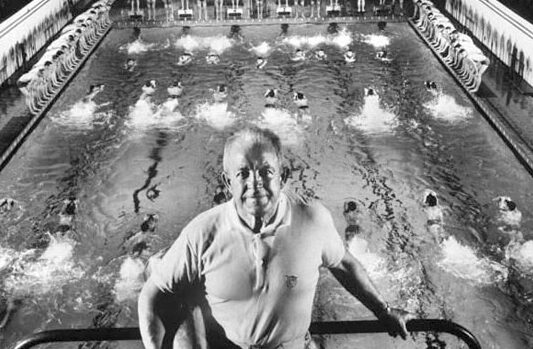

Today We Remember 1965 Honoree Johnny Weissmuller on His Birthday!!

Johnny Weissmuller (USA)

Honor Swimmer (1965)

The information on this page was written the year of their induction.

FOR THE RECORD: OLYMPIC GAMES: 1924 gold (100m, 400m freestyle; 4x200m freestyle relay), bronze (water polo); 1928 gold (100m freestyle; 4x200m freestyle relay); WORLD RECORDS: 51; U.S. NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: 52; Played Tarzan in 16 movies.

Johnny Weissmuller holds no current world swimming records and by today’s Olympic standards, you might say he never swam very fast, but you can’t get anyone who ever saw him swim say that there never was a greater swimmer. This was the verdict of 250 sportswriters at A.P.’s mid-century poll and it is still the verdict 15 years later.

He was the swim great of the 1920’s Golden Age of Sports, yet because of the movies and TV, he is as much a part of the scene in the 1960s as he was in the 1920s when his name was coupled with sports immortals such as Babe Ruth, Bill Tilden, Bobby Jones, Jack Dempsey and Red Grange. He is the only one of this group more famous today than in the “Golden Age.”

Weissmuller set many world records and won 5 gold medals in two Olympics (1924 and 1928). He never lost a race in 10 years of amateur swimming in distances from 50 yards to 1/2 mile. Johnny’s 51 seconds 100 yard freestyle record set June 5, 1927, in the University of Michigan Union Pool stood for 17 years until it was broken by Alan Ford at Yale in 1944. The 100 yd. distance is swum more often than any other, yet in 17 years, only one man ever swam it faster. That man was Johnny Weissmuller, who later, as a professional in the Billy Rose World’s Fair Aquacade swam 48.5 at the New York Athletic Club while training Walter Spence to win the nationals. For those who think swimmers must be teenage bobby-soxers, it might be of interest to note that Spence was 35 at the time and Weissmuller was 36.

His record of 52 national championship gold medals should stand forever. He is famous for his chest high crawl stroke seen by millions in Olympic swim stadiums, on movie screens and on TV, but he also held world records in the backstroke and never lost a race in that stroke. “I got bored,” says Johnny, “so I swam on my back where I could spend more time looking around.” Weissmuller set 51 world records in his ten years as an amateur but many more times he broke world records and never turned in the record applications. Every time he swam, the crowd expected a new record, so Johnny learned pace. He learned how to shave his records a tenth of a second at a time. If he missed, his 350 lb. coach Bill Bachrach would say “rest a few minutes, Johnny, and we’ll swim again.” Bachrach would promise his protégé a dinner if he broke the record and Johnny always seemed to be hungry. Many a world mark was set with only a couple of visiting coaches or a few guests of the Illinois Athletic Club to watch.

Every old-timer in swimming has a favorite Johnny Weissmuller story. To them all, he was the world’s greatest swimmer, yet ironically the producer who signed him to play Tarzan didn’t know Johnny could swim. “Many think I turned pro to go into the movies,” Johnny says, “but this is not true. I was working for a bathing suit company for $500 a week for five years, which was not bad money then (or now). I was in Los Angeles and they asked me if I would like to screen test for Tarzan. I told them ‘no thanks’ but they said I could go to the MGM lot and meet Greta Garbo and have lunch with Clark Gable. Any kid would want to do that so I said ‘okay’. I had to climb a tree and then run past the camera carrying a girl. There were 150 actors trying for the part, so after lunch, I took off for Oregon on my next stop for the swim suit outfit. Somebody called me on the phone and said ‘Johnny, you got it.’ ‘Got what?’ ‘You’re Tarzan.’ ‘What happened to those other 150 guys?’ ‘They picked you.’”

“So the producer asked me my name and he said it would never go. ‘We’ll have to shorten it,’ he said. ‘Weissmuller is to long. It will never go on a marquee.’ The director butted in. ‘Don’t you ever read the papers?’ he asked the producer. ‘This guy is the world’s greatest swimmer.’ The producer said he only read the trade papers, but okay, I could keep my name and he told the writers, ‘put a lot of swimming in the movie, because this guy can swim.’”

“So you see why I owe everything to swimming,” Weissmuller says. “It not only made my name, it saved my name. Without swimming, I’d be a nobody. Who ever heard of Jon Weis, marquee or no marquee.”

Besides swimming, Johnny Weissmuller played on two U.S. Olympic water polo teams. “Water polo’s a rough game,” Johnny says. “We never could beat those Yugoslavians. They never blow a whistle over there. Anyhow, that’s where I learned to duck. It came in handy when Cheetah started throwing coconuts.”

The Story of Charles Jackson French – A Hero For Our Time

by Bruce Wigo

26 May 2025

The Story of Charles Jackson French – A Hero For Our Time

On January 19, 2020, the United States Navy announced it was naming a new aircraft carrier after African American WWII war hero “Dorie” Miller. The announcement came more than 78 years after the events at Pearl Harbor that earned him the Navy Cross, the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps’ second-highest military decoration awarded for sailors who distinguish themselves for extraordinary heroism in combat with an armed enemy force. The U.S.S. Doris Miller is seen as a belated salute to the contributions of African Americans in the military. But it is just a first step. There is another Navy man who was at least equally heroic and deserves recognition.

The world first heard about this story on October 21st, 1942, when U.S. Navy Ensign Robert Adrian was in the Hollywood studios of the NBC Broadcasting Company. He was there for a weekly radio program called, It Happened in the Service. “For the past week,” the solemn sounding host began, “the prayers of the nation have been turned toward the Solomon islands, a small group of strategic islands in the South Pacific. Right now, one of the greatest battles of history is raging there and in the waters of the surrounding islands, and here in our studio tonight is a gallant naval officer who has already tasted the fury of that Solomon battle and who has had his ship blasted out from under him. But before we meet Ensign Robert Adrian, let’s listen to his story.”

That was the cue for dramatic organ music and the sound of sirens and explosions. Amidst those cacophonous sounds came a voice calmly announcing: “Abandon ship, all hands, abandon ship.” Adrian was the junior officer on the bridge when it took a direct hit from a Japanese ship. He was knocked unconscious for a moment and when he came to, he felt the ship turning on its side and sinking. Although wounded in his legs and with blast fragments in his eyes that clouded his vision, he managed to float over into the water with his life jacket as the ship sank below him. As he drifted, he saw the Japanese ships turn their searchlights and machine guns on the survivors. Then he heard voices and found a life raft filled with badly wounded shipmates. Upon questioning the men, he found only one shipmate who had not been wounded. It was Charles Jackson French, a negro mess attendant known only by his last name. When Adrian told French that the current was carrying them toward the Japanese occupied island, French volunteered to swim the raft away from shore. Adrian told him it was impossible – that he would only be giving himself up to the sharks that surrounded them. But French responded that he was a powerful swimmer and was less afraid of the sharks than he was of the Japanese. He stripped off his clothes, asked for help to tie a rope around his waist and slipped into the water. “Just keep telling me if I’m goin’ the right way,” he said. French swam and swam all night, 6 to 8 hours and pulled the raft well out to sea. At sunrise, they where spotted by scout aircraft who dispatched a marine landing craft to pick them up and returned them safely behind American lines.

When the dramatization ended, the host returned to the microphone: “And now standing here beside me is Ensign Bob Adrian of Ontario, Oregon. Ensign, yours was certainly an unusual rescue.”

“Yes, it was,” agreed Adrian. “And I can assure you that all the men on that raft are grateful to mess attendant French for his brave action off Guadacanal that night.”

“Well, he is certainly a credit to the finest traditions of the Navy.”

Adrian was then prompted to give a patriotic enlistment appeal and for everyone at home to unite behind the war effort.

Photo Courtesy:

The next day, the Associated Press picked up the story of the “powerful Negro mess attendant who swam six hours through shark-infested waters, towing to safety a raft load of wounded seamen.” The story reached Philadelphia and the War Gum Trading Card Company, which as the name suggests, sold bubble gum with commemorative baseball-like cards depicting the war’s heroes and events. The card, captioned as: “Negro Swimmer Tows Survivors,” was #129 in the 1942 set. It has a beautiful color rendition of French towing the raft of wounded seamen in wavy blue water with two shark fins near the raft. The flip side told the story, without knowing the identity of the hero beyond being a “Negro mess attendant, known only as ‘French.’” It went on to say that because Ensign Adrian was immediately hospitalized, he “never learned the full name of the heroic swimmer.”

Then, on October 30th, NBC revealed it had learned about French through the Navy Personnel Bureau in Washington. He was 23-year-old Charles Jackson French, of Foreman, Arkansas. The revelation brought a passionate editorial reaction from the Pittsburgh Courier, one the nation’s leading Black newspapers.

“All those who thrill to high HEROISM are paying tribute to a black boy from Arkansas, who risked his life that his white comrades might live. We did NOT learn about this act of heroism… from the Navy Department. We learned about it almost incidentally, from Ensign Robert Adrian, white officer of the destroyer Gregory…when he broadcast over an NBC national hookup from Hollywood. He and other white Americans owe their LIVES to a black man whom he identified as a ‘mess attendant named French.’ Mess attendants are none too highly regarded in the United States Navy. They are either Negroes or Filipinos and they are BARRED from service in any other branch of the Navy unless serving in a segregated unit. There is not much OPPORTUNITY for heroism in a ship’s galley or an officers’ ward room. But all the men on a ship are in DANGER in time of battle, no matter where they are serving or what their skin pigment may be…Although Mess Attendant Charles Jackson French of Arkansas was not in a heroic job, he MADE a heroic job out of it. He who had been looked down upon as a caste man, frozen in status, suddenly was looked up to as a SAVIOUR.”

It also described what happened prior to Adrian finding the raft. That French had found the raft floating and had swum around with it, piling “wounded white comrades upon it until it had almost sank.”

“All men honor bravery and LOYALTY, and today all America hails ‘A Mess Attendant named French” who risked death that others might live. Americans like Mess Attendant French and Ensign Adrian, mutually undergoing danger to preserve American freedom for all alike, will make democracy a glowing reality in this country for future generations to enjoy.”

In time it was learned that Charles Jackson French stood 5’8” tall and weighed 195 pounds. He had been born on Sept. 25, 1919, in Foreman, Arkansas. But after his parents died, he moved to Omaha, Nebraska to live with his sister. On December 4, 1937, French enlisted in the Steward/Messman branch of the United States Navy – the only positions open to African Americans at the time. He was assigned to the USS Houston, the flagship of the Asiatic Fleet. As a Mess Attendant 3rd class, his job was to serve meals to white officers and sailors, clear their tables and keep the mess, not a mess. While French was onboard, the Houston was stationed in Hawaii and cruised the Pacific Ocean with stops in the Philippines and Shanghai, to name a few. After his four year commitment ended in 1941, French returned to 2703 North 25th St. in Omaha, Nebraska. But four days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, French re-enlisted as a Steward’s Mate 1st class. He joined the crew of the USS Gregory in March of 1942. Although Stewards were a step up from mess mates, they were derisively labeled “seagoing bellhops” by the black press. Their job was to man the white officers’ mess and clean their quarters.

Back in the USA after the sinking of the Gregory, the “human tugboat” visited relatives in Foreman and received a royal welcome from citizens of all races in Omaha. He appeared before enthusiastic crowds at the halftime of a Creighton football game, at war bond rallies, on a calendar and in newspaper comic strips. There was even talk of a Hollywood film.

In early 1943, Twentieth Century Fox released the film adaptation of the Broadway musical,“Stormy Weather”with an all-black cast of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, Katherine Dunham and Fats Waller. In June, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer brought to the big screen “Cabin in the Sky,” another musical with an all-black cast that included Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Ethel Waters and Lena Horne. Both were hits. “However,” reported the Pittsburgh Courier, “Warner Brothers has it in mind to go all of the companies one better and screen-Immortalize Messman French, the lad who swam through shark-infested waters, towing a raft of wounded sailors to safety after a Japanese sub had sunk their ship in the South Pacific.”

Photo Courtesy:

Based on his incident report, Ensign Adrian had been informed that Mess Attendant French was being recommended for the Navy Cross. It was the second highest honor, just below the Congressional Medal of Honor, and it was the medal that had been awarded to Doris Miller. Then in December of 1943, French’s heroism was immortalized in a poem written entitled “The Strong Swimmer,” by the 1942 Pulitzer Prize recipient, William Rose Benet.

THE STRONG SWIMMERby William Rose Benet*

I have a story fit to tell,In head and heart a song;A burning blue Pacific swell;A raft that was towed along.

Out in the bloody Solomon IslesDestroyer Gregory gone;Ocean that kills for all her smiles,And darkness coming on.

The Gregory’s raft bobbed on the tideLoaded with wounded men.Ensign and seaman clung her side.Seaward she drifted then.

A mess-attendant, a Negro man,Mighty of chest and limb,Spoke up: “Til tow you all I canAs long as I can swim.”

Naked, he wound his waist with a line;Slipped smoothly overside,Where the red bubble tells the brineThat sharks have sheared the tide.

‘I’m going to tow this old craft inSince we ain’t got not one oar’He breathed, as the water lapped his chin;And he inched that raft ashore.

Strongly he stroked, and long he hauledNo breath for any song.His wounded mates clung close, appalled.He towed that raft along.

Clear to the eye the darkening swellWhere glimmering dangers glide;The raft of sailors grimed from HellAfloat on a smoky tide

And a dark shoulder and muscled armLunging, steady and strong.The messman, their brother, who bears a charm,Is towing their raft along.

He gasped, “Just say if I’m go’in right!”Yes, brother, right you are!Danger of ocean or dark of night,You steer by one clear star.

Six hours crawled by. … A barge in sightWith the raft just off the shore. . . .The messman coughed, “Sure, I’m all right’He was just as he was before.

And all that they knew was they called him “French*Not quite a name to sing.Green jungle hell or desert trench,No man did a braver thing.

He’s burned a story in my brain,Set in my heart a song.He and his like, by wave and main,World without end and not in vainAre towing this world along!

From “Day of Deliverance,” copyright, 1944, by William Rose Benet.

A significant award for heroism seemed assured, but it wasn’t to be. All he would receive was a letter of commendation from Adm. William F. Halsey, Jr., then commander, of the Southern Pacific Fleet. It read: “For meritorious conduct in action while serving on board a destroyer transport which was badly damaged during the engagement with Japanese forces in the British Solomon Islands on September 5, 1942. After the engagement, a group of about fifteen men were adrift on a raft, which was being deliberately shelled by Japanese naval forces. French tied a line to himself and swam for more than two hours without rest, thus attempting to tow the raft. His conduct was in keeping with the highest traditions of the Naval Service.” They were eight hours in the water, but Admiral Halsey reduced it to two.

Ensign Adrian was outraged, but the Gregory episode was complicated by the issuance of a posthumous Silver Star to Lt. Cdr. H. F. Bauer, the ship’s CO. Wounded and dying, the skipper had ordered Adrian and the signalman on the bridge to leave him and go to the aid of another crewman who was yelling for help. He was never seen again. By Navy standards, it would be nearly unprecedented for a subordinate to receive a higher decoration for an act of heroism comparable to that of a superior. In addition to the Silver Star, a Destroyer-minelayer was named the USS Harry F. Bauer in 1944.

Charles Jackson French was probably manning his mop or carrying food trays on the USS Endicott when he heard the news. At the time, his destroyer was escorting convoys in the Atlantic theater, along the African coast and in the Caribbean. With the Endicott needing repairs in May of 1944, French was assigned to the USS Frankford, a destroyer that provided support from its five guns for the successful landings on D-Day, along with rescuing survivors of mined ships and downed pilots, and driving off enemy E-boat attacks. In August, the Frankford arrived in Naples, Italy for the invasion of southern France.

Photo Courtesy:

Little was known of French after the war ended and he was soon forgotten. But sometime after the Korean War, he was at a friend’s home in San Diego and told his side of the story. One of those listening was Chester Wright, who repeated what French said in his book, Black Men and Blue Water. French told it pretty much as Adrian had done years earlier, but with a few twists. He laughed when he told how he almost peed himself when he felt the sharks brush against his feet, but guessed they weren’t hungry for a scared black man. As he told of raft being rescued, his mood changed from jovial to anger and tears. After the badly wounded men were taken to the hospital, French and the others were taken to a rest camp where authorities wanted to separate French because he was “colored.” The white boys from the raft and some of the other survivors from the Gregory refused to have him separated. He was a member of the Gregory’s crew, they said, and they were going to stay together. Anyone who thought different had better been better been ready to fight. There was a standoff that lasted some time, with the crew of the Gregory, all covered with oil and grime and looking like madmen, facing off against the masters at arms in their clean and pressed whites. Eventually, they realized the Gregory’s crew meant what they said and backed down. As French told this part of the story, his shoulders shook and tears coursed down his cheeks as he told how the white boys had stood up for him.

According to Wright, French had returned from the war “stressed out,” from seeing too much death and destruction. He was probably discharged with mental problems and left to fend for himself. He died on November 7, 1956 and was buried in the Fort Rosencrans National Cemetery, in San Diego, an almost forgotten hero.

The name of Charles Jackson French resurfaced in 2009, when his story was part of an exhibit on Black Swimming History at the International Swimming Hall of Fame, in Fort Lauderdale. The irony of French’s heroics was that it came at a time when African Americans were prevented from swimming in virtually every swimming pool and public beach in America. When he was being celebrated in Omaha in 1943, there was no pool in the city where he could have taken a dip. So one of the questions that remain is where and how did he become such a powerful swimmer? Unfortunately his surviving relatives don’t have the answer. The best guess is in the Red River and stone quarries near Forman, Ark.

About ten years later, the exhibit came to the attention of a retired Navy couple, who began some research of their own. They found the family of Robert Adrian, who had passed away in 2011, but his family had their own story to tell of Charles Jackson French. Their father rarely spoke of his war experiences, except for French, for if not for a black man named Charles Jackson French, he would tell them, neither he nor any of them would be alive. For his 75th Birthday, Adrian’s children had found an old record amongst their father’s treasures. It had been given to him by NBC back in 1943. It was the recording of It Happened In the Service. Hearing it after all those years brought him to tears.

Adrian had tried to locate French after the war with no success, but he also had suffered another trauma. It was almost exactly a year after the sinking of the Gregory and he was the gunnery officer on the the destroyer USS Boyd, when it came under attack. As the crew was helping to rescue a downed pilot, two enemy shells crashed into the ship, destroying the forward guns and exploded in the engine room, bursting the steam pipes. One officer and eleven men were killed and another eight seriously wounded. It was Adrian who led the rescue team and he had recurring nightmares the rest of his life seeing the bodies of those men burned alive by 800 degree heat. He was at sea for much of his carrier followed by a successful career as a banker.

After his second retirement, he began writing and one of the stories was published in Tin Can Alley, a newsletter that appealed to men who served on destroyers. It was called, Our Night of Hell off Guadalcanal and it told the story of the Gregory and French and his recommendation for the Navy Cross. He spoke about French to Navy Brass, but social justice was not the issue it is today. He had hoped that before he died, French would receive the commendation he deserved, but since it wasn’t he told his children to carry on with his dying wish.

Then in April of 2021, an online post about French from the International Swimming Hall of Fame caught the attention of Rear Admiral Charles Brown, the Navy public affairs officer who said the Navy will see if “it can do more to recognize Petty Officer French.”

In Washington, Nebraska Congressman Don Bacon said that he believed French deserved the Congressional Medal of Honor.

In January of 2024, the United States Navy announced that it will name a ship after Charles Jackson French. The announcement was made by Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro during a keynote address at the Surface Navy’s 36th National Symposium in Arlington, Virginia. The U.S.S. Charles J. French will be an Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer.

In fairness and with impartiality a destroyer should be named after French if not the medal of honor set the record straight !!! America home of the free and the brave. Show that the content of a person’s character and not the color of their skin. That is why the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA is the greatest nation in the world *****

Memorial Day Weekend: How World War II Impacted Yale Coaching Legend and ISHOF Honoree Bob Kiphuth

by Swimming World Editorial Team

26 May 2025

Memorial Day Rewind: How World War II Impacted Yale Great Bob Kiphuth

Editor’s note: We are reposting this great feature by Chuck Warner, originally written as part of a series of articles about the great Yale coach Bob Kiphuth, highlighting a moment in Kiphuth’s career that intersected with the rise of World War II. It fits well with this Memorial Day Weekend to take a look back.

By Chuck Warner

As Coach Bob Kiphuth drove across the George Washington Bridge he might have gazed up and down the Hudson River. The New York City skyline was magnificent in its height as well as breadth. Kiphuth loved grand experiences, which is one of the reasons why the Yale Water Carnival was such a joy for him to produce and direct each year. But in those early years when the new Payne Whitney Gym housed the Carnival it was also a time when the strength of the USA Olympic swimming teams was challenged. Coach Kiphuth was a patriot. He openly expressed his concern that America was too directed toward short course swimming and ill-prepared to race as successfully in a long course pool in international competition.

In 1931 Coach Kiphuth made his first trip to Japan. The passion that the Japanese had for swimming was stunning. They hadn’t begun participating in Olympic swimming competition until 1920, but were earnest in their desire to become more competitive. Nearly every year they invited the best swimmers in the world to perform exhibitions in their country. Johnny Weissmuller made several trips and became a model that Japanese coaches studied endlessly. When Kiphuth took a swimmer to the Japanese pool for an exhibition in 1931, there were 40,000 fans in the stands.

At the 1932 Olympics in Los Angeles a youth brigade from Japan put on one of the most dominating swimming performances in men’s swimming history. Kuzono Kitamura, 14, led a 1-2-3 sweep in the 1500-meter freestyle. Yasuji Miyazaki, 15, teamed with 20-year old Tasugo Kawaishi to finish 1-2 in the 100-meter freestyle. Before they were finished the Japanese men would win five gold medals out of a possible six, five silver medals out of possible six and add another two bronze medals.

What was the secret of the Japanese success? Studies done by Forbes Carlisle show Japanese coaches talking about the advantage of swimming with short strokes and having loose ankles to be good kickers. Weissmuller didn’t swim with short strokes, but their observations about what made a good kick would be applicable today. The greatest discovery the Japanese seemed to have made was the benefits of hard work.

For three months of training each year in Japan, they had swum twice a day covering 6,000-7,500 meters per day. This was an enormous increase from the 400-meter training days that Weissmuller and his coach Bill Bachrach had insisted was optimal. In the context of the 1930s the Japanese showed that work does work.

American Helene Madison led a superb performance by the American women in 1932 in which they won four of the available five gold medals. By the 1936 Games, however, the Netherlands had over taken the Americans to dominate women’s swimming. The Japanese men were not as dominant but still the best in the world in Berlin.

The Olympics in Germany were more than a stage for sport. They were the opening act for World War II, the most widespread war in history. Observing the Olympic track events was German Chancellor Adolf Hitler. Hitler’s anti-Semitic beliefs were well-known and his belief in the superiority of the German and Aryan racial superiority was being challenged by the performance of Jesse Owens in track and field. Owens was an African-American who eventually won four gold medals. But it was his second one that might have been the most remarkable. While Hitler looked on, German Luz Long was positioned to beat Owens for the gold medal in the long jump. Owens had faulted on his first two jumps taking off past the wooden plank on the track that marked the appropriate takeoff point. In a show of what has long been held as the ‘true Olympic spirit,’ Long took a towel and laid it down a few inches or so before the wooden plank. Owens used the towel cue, performed legally and won the long jump.

Long was the first to greet Owens after the win. Owens’ long jump world record stood for nearly 24 years. The two athletes maintained a friendship until Long was killed in World War II.

In 1937 the Japanese emperor invaded China. In 1939 Germany invaded Poland. The war was on.

More than 100 million people joined and fought in the military over the next six years during the awful ordeal. One was Yale’s Dick Baribault. Baribault was a member of Yale’s record-setting 4 x 100 freestyle relay when he enlisted into the United States Air Force. Why enlist? He believed in the cause of defeating Hitler, but it was also evident that he would be drafted to fight. By enlisting there was a chance to choose your military branch of service.

“Your best chance to survive was to stay away from the land battles that the Army would be engaged in,” Dick said years later. Eventually he returned to Yale to swim. “After machine gun battles in the air against the Germans, nothing Kiphuth had us do in training scared me.”

The 1940 and 1944 Olympics were canceled due to the War. The Japanese were banned from participating in the 1948 Games opening the door for the most dominant performance by an Olympic men’s team in history. The head coach for the USA in 1948? The man steering his car down the New Jersey Turnpike in the direction of Washington D.C.: Robert John Herman Kiphuth.

Story help from the work of Pete Kennedy and Forbes Carlisle.

June Featured Honoree: Terry Schroeder (USA) and his Memorabilia

Each month ISHOF will feature an Honoree and some of their aquatic memorabilia, that they have so graciously either given or loaned to us. Since we are closed, and everything is in storage, we wanted to still be able to highlight some of the amazing artifacts that ISHOF has and to be able to share these items with you.

We continue in June 2025, with 2002 ISHOF Honoree, Terry Schroeder Honor Water Polo. Terry donated many fabulous things to ISHOF and we want to share some of them with you now. Also below is his ISHOF Honoree bio that was written the year he was inducted.

ISHOF Honoree Dawn Fraser Back In the Pool As The Swimmer Of The Century Faces The Greatest Challenge Of Her Life

HAPPY PLACE: Dawn Fraser is back swimming as she faces the greatest challenge of her life. Photo Courtesy: Swim Australia.

by Ian Hanson – Oceania Correspondent

14 May 2025

Dawn Fraser Back In the Pool As She Faces The Greatest Challenge Of Her Life

Olympic legend Dawn Fraser has revealed that doctors told her “she could die” on the operating table following a fall at her Noosa home last December as she takes to the pool again for her greatest challenge.

The 87-year-old four-time Olympic champion has been fitted with a pacemaker after a feinting episode – the heart that took her to the top of the world – momentarily stopped beating.

Named the Swimmer of the Century, Dawn has appeared on Australian television in an exclusive interview – with vision of the three-time Olympic 100m freestyle gold medallist back in the pool on the Queensland Sunshine Coast – therapy for her post operative hip surgery and heart scare.

Demonstrating that famous stroke that took her to three consecutive Olympic 100m freestyle gold medals in 1956, 1960 and 1964.

“Our Dawn” in her happy place as she turns the clock back, rehabbing from a frightening fall that resulted in four broken ribs and a broken hip – and dealing with the prospect that she may die on the operating table.

“The doctor said I could die. It wasn’t a safe operation…that was the frightening part…that I might die under anesthetic, and I didn’t want to die that way…” Dawn told Ten Eyewitness News, comforted by her daughter Dawn Lorraine and grandson Jackson.

“So I wasn’t going to give in…especially away from my family.”

Dawn surviving the operation but later suffering a feinting episode – subsequently fitted with a pacemaker which is monitored remotely 24 hours a day.

“I started to feel very feint and then I feinted, and they said my heart had stopped for five seconds and I had a very low heart rate,” said Dawn, who also struggled with depression, losing 22 kilos in weight, told she is not to drive anymore and that she must slow down.

“I’m back in water and doing exercises I used to do when I was training, and it kept me going. It is very important for your health and for my family too.”

Dawn knowing that being back in the pool is the best tonic she could have as the Olympic golden girl races the clock again in the fight of her life.

And as frail as she may be, one thing is certain, Dawn Fraser isn’t going to miss next month’s World Championship Swimming Trials in Adelaide.

She is planning on being on pool deck to cheer on the current day champions…also saying that the Brisbane 32 Olympic Games isn’t out of the question.

“I hope so..I’ll be 95 then..” said Dawn.

A Week of Katie Ledecky Stats (Day Four): Distance Ace Has Made Sub-4:00 Her Home in 400 Freestyle

by John Lohn – Editor-in-Chief

14 May 2025,

A Week of Katie Ledecky Stats (Day Four): Distance Ace Has Made Sub-4:00 Her Home in 400 Freestyle

In recognition of Katie Ledecky lowering her world record in the 800-meter freestyle to 8:04.12, Swimming World continues its Week of Katie Ledecky Statistics. Each day for a week, we are running a short piece that highlights Ledecky-related stats, numbers that place additional context on her legendary career.

There’s no debate that the 800-meter freestyle and 1500 freestyle are recognized as Katie Ledecky’s premier events, with the 400 freestyle solidly slotted in the No. 3 position. Since capturing Olympic gold in the 400 freestyle at the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, Ledecky has been eclipsed in the discipline by Ariarne Titmus. The Australian ace has won the past two Olympic titles, with Ledecky earning silver and bronze in Tokyo and Paris.

Yet, Ledecky remains the most-decorated female in terms of sub-4:00 performances, a time that has been cracked by only five women in history – Federica Pellegrini, Ledecky, Titmus, Summer McIntosh and Erika Fairweather. Of the 56 all-time marks under four minutes, 31 belong to Ledecky. That total accounts for 55.35% of the historical sub-4:00 efforts. Next on the list is Titmus with 13 trips under four minutes, followed by McIntosh with nine.

Ledecky’s personal best in the 400 freestyle sits at 3:56.46, her winning time in the Olympic final in Rio. Earlier this month, she clocked the second-fastest time of her career, a 3:56.81 showing at the TYR Pro Series in Fort Lauderdale. Ledecky has been sub-4:00 at least once in 13 consecutive years, a streak that began in 2013.

Great Races: When Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner Broke a Special Barrier – A Unique Summer Pursuit Of Sub-50

by John Lohn – Editor-in-Chief

26 April 2025

When Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner Chased Sub-50: A Unique Summer Pursuit

Swimming World’s Great Races Series has featured numerous duels between star athletes. In this edition, Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner engaged in a great race, albeit one in separate pools.

The most iconic barrier-breaking performance in sports history is not difficult to decipher. It is the 3:59.4 mile run by Great Britain’s Roger Bannister in 1954, marking the first time the four-minute threshold was eclipsed. The effort captured the attention of the world and opened the imagination of what was possible in an athletic endeavor.

Fourteen years later, American sprinter Jim Hines produced another legendary outing, as he became the first man to officially cover the 100-meter dash in under 10 seconds. The speed Hines displayed in 1968 handed him the gold medal in the event at the Olympic Games in Mexico City.

From the equine world, Secretariat is celebrated as the greatest racehorse of all-time and used the 1973 Kentucky Derby to put on a show that remains unmatched. Running 1:59.40 at Churchill Downs, Big Red – as he was known – became the first horse to crack the two-minute barrier in the Derby, which is run on a 11⁄4-mile track. His Triple Crown was completed several weeks later, when he delivered his epic run at the Belmont Stakes

In the pool, breaching the 50-second barrier in the 100-meter freestyle became a major storyline of 1976. The men at the center of the chase, American Jim Montgomery and South African Jonty Skinner, never met during that Summer of Speed, as politics kept them apart. Nonetheless, they engaged in an entertaining, albeit long-distance, duel.

The 100 freestyle has long been considered swimming’s blue-ribbon event, and the territory of some of the sport’s legends. Duke Kahanamoku, Johnny Weissmuller, Don Schollander and Mark Spitz, to name a quartet, won Olympic gold in the two-lap discipline. More, Weissmuller was the first man to break the one-minute barrier, accomplishing the feat in 1922. Over the next half-century, the record continued to dip, to the point where sub-50 became a legitimate possibility midway through the 1970s.

In most eras, the Olympics bring together the best competitors an event has to offer. However, that was not the case at the 1976 Games in Montreal, where a key figure was missing from the pool deck. Four years before President Jimmy Carter infused politics into sports by leading a United States boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, politics played a role in the 1976 Games.

Due to its apartheid policies, South Africa was banned from the Olympic Games by the International Olympic Committee in 1964, a restriction that lasted until the 1992 Games. Caught in the middle of his country’s segregation practices, which he did not support, was Skinner, one of the world’s premier sprint freestylers.

Competing collegiately for the University of Alabama, Skinner established himself as an NCAA and United States national champion in the 100 freestyle. As much as Skinner might have been detached from his homeland and apartheid, his citizenship – based on IOC rule – made Skinner ineligible to compete on the biggest stage in sports. It was a hand Skinner was forced to accept, and it also dealt a blow to the depth of the 1976 Games. Without Skinner, Montgomery raced the clock, and not a rival who would have raised the level of competition.

As he prepared for the Montreal Games, Montgomery was a well-known commodity. In 1973, Montgomery flourished as a member of Team USA at the inaugural World Championships. In Belgrade, Yugoslavia, Montgomery earned gold medals in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle, and helped the United States win three relay titles.

Following the World Champs, Montgomery joined the power program of Indiana University, which was guided by Hall of Fame coach Doc Counsilman. As a Hoosier, Montgomery captured three individual NCAA titles and developed into an Olympian, thanks to Counsilman’s influence. Although Montgomery exhibited natural ability before working with Counsilman, the coach enabled Montgomery to hone his mental approach.

Jim Montgomery

Ahead of the Olympics in Montreal, Counsilman convinced the men’s team that it could establish itself as the greatest team in history. Indeed, that is what Team USA accomplished, as it won 12 of the 13 events and swept the podium in four disciplines.

“He’s the smartest guy I’ve ever known in my entire life,” Montgomery said of Counsilman. “Just sheer brain power. And he had a sense of humor. He just put it right on the plate. ‘We’re going to absolutely dominate. That’s my goal, and that’s my goal for you guys.’”

Montgomery personally accepted Counsilman’s challenge.

Coming off a bronze medal in the 100 freestyle from the 1975 World Championships, Montgomery elevated his performances in Montreal, a fact that was evident during the semifinals of the 100 freestyle. Erasing any doubt over who was the favorite for gold, Montgomery blistered a world record of 50.39, a mark which was nearly more than a second faster than the No. 2 seed, Italian Marcello Guarducci (51.35). Montgomery’s dominance allowed he and Counsilman to experiment in the final.

“After the prelims, we figured we had the race pretty much won,” Counsilman said. “So we risked it. We swam the race to break the record by going out harder. We figured that even if he died a little coming home, he’d still have enough to win.”

Montgomery and Counsilman were not just concerned with lowering the world record. The final was about taking Montgomery into – pardon the pun – uncharted waters. A sub-50 performance was within reach and producing a readout on the clock that started with a “4” was an enticing opportunity.

As a member of a squad that was obliterating the opposition, there was a competition within a competition of sorts for Team USA. Who could produce the most memorable performance? For that honor, the battle primarily came down to Montgomery and John Naber, the University of Southern California star who won the 100 backstroke and 200 backstroke events in world-record time. Montgomery, though, had the extra power of delivering a barrier-breaking outing.

The bronze medal Montgomery claimed in the 100 freestyle at the 1975 World Champs also served as motivation. During 1974 training, Montgomery and Counsilman toyed with a workload that was more geared toward the middle-distance events. Ultimately, it cost Montgomery some of his pop in his main event, but the error was better realized at the World Champs, rather than the Olympics. By the time Montreal called, Montgomery was in peak form and possessed lofty target times.

“I thought realistically I could swim 49.4 or 49.5,” Montgomery said. “I had some relay splits that were that fast at that time, and back then we didn’t have the fancy relay starts they do now. If I didn’t have that training failure in 1974, I wouldn’t have become Olympic champion. I was stronger and handled the power training necessary for the 100 free.”

The confidence brewed by Counsilman in Montgomery was clear from the start in the final as the 21-year-old bolted to the front of the field and held a half-body-length lead at the turn. Coming off the wall in 24.14, the question wasn’t whether Montgomery would win the race, but if he could join Bannister and Hines as a barrier breaker. Indeed, Montgomery was given access to the club by the slimmest of margins, the scoreboard flashing 49.99. Countryman Jack Babashoff followed in the silver-medal position, well behind in 50.81.

“This will put Montgomery in the Swimming Hall of Fame,” Counsilman said. “I think this is the last barrier in swimming. We broke one minute in the 100 freestyle 50 years ago, and I don’t think we are going to break 40 seconds. So this is it, at least for a long time. I thought it was the best swim of the Olympics, and we’ve had some good swims.”

Counsilman was prophetic in his statement, as Montgomery was enshrined into the International Swimming Hall of Fame as a member of the Class of 1986. While Montgomery’s profile obviously highlights his gold medal, it also references his barrier-breaking identity and place in history alongside Bannister.

Jonty Skinner – Photo Courtesy: Amelia B. Barton

As monumental as it was, Montgomery’s world record and solo status in the sub-50 club was short lived. Without the opportunity to race at the Olympics, Skinner identified the Amateur Athletic Union National Championships in Philadelphia as his focus meet for the summer. Scheduled for three weeks after the Olympics, the competition lacked the firepower present in Montreal, but Skinner wasn’t really racing the men in the adjacent lanes in Kelly Pool. Instead, Skinner was racing the clock and Montgomery.

Before settling on Philadelphia as the stage for his personal Olympics, an attempt was made to get Skinner American citizenship in time to compete at the United States Olympic Trials. A petition with more than 50,000 signatures was sent to Washington, D.C. and Representative Walter Flowers, a democrat from Alabama, introduced a bill to Congress – HR 12257 – that would award Skinner citizenship in time to compete at Trials. Alas, the push on Skinner’s behalf fell through, leaving him as a spectator to the Montreal Games.

“I really had no issues with not being there since I was focused on Philly,” Skinner said. “It ticked me off that (Montgomery) 50, and that is what fueled me the last few weeks getting ready. I had focused on breaking 50 as a season goal, so when (Montgomery) went 49.9, I adjusted to 49.8. I wasn’t nervous at all. I did a lot of visualization to prepare, so I was ready in my mind.”

Racing alone or without rivals to push the pace is not an easy chore, but Skinner had plenty of motivation. Despite besting the field by more than two seconds, Skinner relented. He went out in 23.83, .31 quicker than the split of Montgomery, and he came home slightly quicker as well. At the touch, Skinner produced a time of 49.44 to shave .55 off Montgomery’s performance from the Olympic Games.

Although an Olympic medal was not draped around Skinner’s neck, the moment was as meaningful. He had an opportunity taken from him for no fault of his own, but Skinner turned his situation into a positive. His world record was so impressive, it last nearly five years, until Rowdy Gaines clocked 49.36 in April 1981. As impressive, Skinner’s time would have won Olympic gold in 1980 and 1984 and would have earned the bronze medal at the 1988 and 1992 Games.

“Coach, I did it,” said Skinner to his coach at the University of Alabama, Don Gambril. “Since I couldn’t swim against (Montgomery), my opponent had to be the clock. I just kept telling myself, ‘This is your only chance. Don’t blow it.’”

Linked by the Summer of 1976, Montgomery and Skinner have remained involved in the sport in prominent ways. Montgomery followed his Olympiad by winning the silver medal in the 100 freestyle at the 1978 World Championships and, following a brief retirement, started training for the 1980 Olympic Trials, a pursuit that ended when the American boycott of the Moscow Games was announced. Montgomery eventually shifted into Masters competition and has operated swim clubs and swim schools.

As for Skinner, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1985, he took his skills in the water to the deck and a coaching career. Skinner served as the first coach of USA Swimming’s Resident National Team at the United States Olympic Training Center and later held the role of USA Swimming’s Director of Performance Science and Technology. The latter role is one he also held for British Swimming. Before retiring in 2020, Skinner returned to the college ranks, serving as an assistant coach for the University of Alabama, and then Indiana University.

“I could always talk from experience when it came to helping swimmers prepare for peak-level events,” Skinner said of the transition from elite athlete to coach. “I very rarely talked about (his world record in Philadelphia), but the athletes knew my background, so they trusted my opinions.”

Montgomery and Skinner each had his moment to shine, and history looks back favorably at each career. Montgomery will always have his Olympic gold medal. Skinner will always have his day, Aug. 14, 1976, as proof of overcoming disappointment and factors beyond one’s control. There is room to honor both men.

“The Olympics were one day, and this was another,” Skinner said. “But I hope Jim was watching me on TV.”

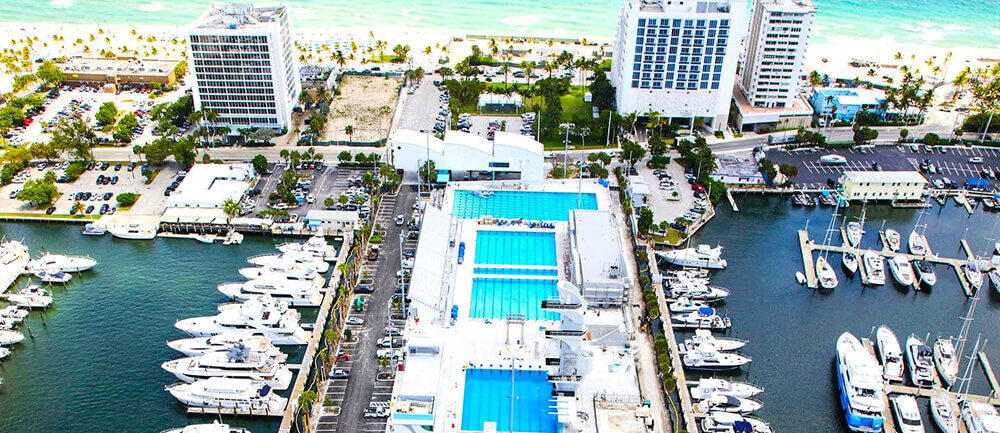

Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex Once Again a World-Record Centerpiece (A List of the Records)

by John Lohn – Editor-in-Chief

04 May 2025

Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex Once Again a World-Record Centerpiece

The Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex, originally built in 1965, has been no stranger to world records through the years. Some of the biggest names in the sport have competed at the venue since its unveiling, including numerous members of the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Simply, Fort Lauderdale is a destination for elite athletes in the sport, and that fact was on display over the past four days.

The USA Swimming TYR Pro Series was held from Wednesday through Saturday at the renovated facility, with sensational performances highlighting each day of action. Notably, Fort Lauderdale returned to world-record status when Katie Ledecky lowered her global standard in the 800 freestyle to 8:04.12 and Gretchen Walsh twice set world records in the 100 butterfly, first going 55.09, and then 54.60.

Thanks to the efforts of Ledecky and Walsh, the Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex now boasts 13 world-record swims in its history. The first record was set by Catie Ball in the 100-meter breaststroke in 1966, with the last before this weekend set by Michael Phelps in the 400 individual medley in 2002. The latter race featured Phelps and Erik Vendt both going under the previous world record.

Here is a look at the 13 world records set at the Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex

Catie Ball (100 Breaststroke: 1:15.60) – 1966Pam Kruse (400 Freestyle: 4:36.80) – 1967Andy Coan (100 Freestyle: 51.11) – 1975Mary T. Meagher (200 Butterfly: 2:08.41) – 1979Mary T. Meagher (200 Butterfly: 2:07.01) – 1979Kim Linehan (1500 Freestyle: 16:04.49) – 1979Martin Zubero (200 Backstroke: 1:57.30) – 1991Mike Barrowman (200 Breaststroke: 2:10.60) – 1991Natalie Coughlin (100 Backstroke: 59.58) – 2002Michael Phelps (400 Individual Medley: 4:11.09) – 2002Gretchen Walsh (100 Butterfly: 55.09) – 2025Katie Ledecky (800 Freestyle: 8:04.12) – 2025Gretchen Walsh (100 Butterfly: 54.60) – 2025

May Featured Honoree: Dorothy Poynton (USA) and her Memorabilia

Each month ISHOF will feature an Honoree and some of their aquatic memorabilia, that they have so graciously either given or loaned to us. Since we are closed, and everything is in storage, we wanted to still be able to highlight some of the amazing artifacts that ISHOF has and to be able to share these items with you.

We continue in the new year, April 2025, with 1968 ISHOF Honoree, Dorothy Poynton Honor Diver. Dorothy Poynton donated many fabulous things to ISHOF and we want to share some of them with you now. Also below is his ISHOF Honoree bio that was written the year he was inducted.

Commemorative Medal awarded to Dorothy Poynton from Mayor LaGuardia for 3m Springboard Diving

1932 Participant medal, 1936 Participant medal, 1936 Gold 10m platform, 1936 Bronze, 1932 Gold 10m p

1 Holborow Swimming Club Medal given to Dorothy Poynton from her Coach Frank Holborow

Pro Swim Series Fort Lauderdale: Stacked Field Includes Ledecky, Marchand, Dressel, McIntosh, Douglass, Walsh Sisters (PSYCH SHEETS)

Leon Marchand of France prepares before competing in the Men’s 400m Individual Medley final during the Paris 2024 Olympic Games at La Defense Arena in Paris (France), July 28, 2024.

by Dan D’Addona — Swimming World Managing Editor

24 April 2025

Pro Swim Series Fort Lauderdale: Stacked Field Includes Ledecky, Marchand, Dressel, McIntosh, Douglass, Walsh Sisters (PSYCH SHEETS)

The 2025 TYR Pro Swim Series will make a stop in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, with a meet from April 30-May 3.

The psych sheet has been released for the meet, which is loaded with swimming stars, including Katie Ledecky, Leon Marchand, Summer McIntosh, Caeleb Dressel, Kate Douglass, Lilly King, Hubert Kos, Simone Manuel, Kylie Masse, Penny Oleksiak, Michael Andrew, Shaine Casas, Katie Grimes, Katharine Berkoff, Claire Curzan, Bella Sims, Ilya Kharun and the Walsh sisters.

World record-holder Katie Ledecky headlines the meet and will be joined in the women’s distance events by NCAA champion Jillian Cox.

Ledecky will have a showdown with Canadian Olympic champion Summer McIntosh in the 400 free.

The men’s distance events will feature Olympians Bobby Finke, Aaron Shackell, David Johnston, Kieran Smith and Luke Hobson.

The women’s 100 free might be the most stacked event with 13 Olympians on the list, led by Kate Douglass, Gretchen Walsh and Simone Manuel. They will be joined in the 50 free by Kasia Wasick.

The men’s 100 free is similar, led by Olympians Chris Guiliano, Caeleb Dressel, Hunter Armstrong and Shaine Casas. Dylan Carter and Michael Andrew will add depth to the 50.

The women’s 100 breaststroke will feature Olympians Lilly King, Emma Weber, Douglass and Alex Walsh, while Andrew will lead the men’s event along with international athletes Evgenii Somov and Denis Petrashov. The 50 breaststroke fields will be similar.

The women’s 50 backstroke, now an Olympic event, will feature Regan Smith, Katharine Berkoff, Claire Curzan, Rhyan White and Bella Sims – all U.S. Olympians. If that wasn’t enough, Canadian Olympians Kylie Masse and Taylor Ruck are in the field, too. Armstrong, Hugo Gonzalez, Hubert Kos and Casas lead the men’s event.

Smith and Alex Shackell will lead the 200 butterfly, the two Paris Olympians in the event, while Canada’s Ilya Kharun and U.S. Olympian Carson Foster lead the men’s event.

The women’s 200 free will feature Penny Oleksiak, Claire Weinstein, Ledecky, Sims, Gemmell, Shackell, Manuel, Katie Grimes, Leah Hayes and more.

Hobson, leads the 200 free in a field that has Guiliano, Smith, Foster, Aaron Shackell and Marchand.

Gretchen Walsh, Smith and Douglass will square off in the 50 butterfly. The men’s race will feature Dressel, Kharun, Casas and Andrew. Walsh and Dressel lead the 100 butterfly as well.

The 200 backstroke will see a Smith, White, Curzan, McIntosh and Grimes showdown, while Kos and Gonzalez lead the men’s field.

Marchand leads the field in the men’s 400 IM, 200 IM and 200 breaststroke – by a lot.

Grimes, Emma Weyant and Leah Hayes will square off in the 400 IM.

The women’s 100 backstroke is always stacked. Smith, Katharine Berkoff, Masse, Curzan, White, Ruck and Sims will make sure that trend continues, while Kos, Armstrong and Gonzalez do the same for the men.

Douglass and Alex Walsh will again square off in the 200 breaststroke, while Walsh, Smith and Hayes will do the same in the 200 IM.