Salute to National Women’s Month: Honoree Ethelda Bliebtrey

There are so many strong women in sports, particularly aquatic sports, but in the month of March, we specifically try to really pay tribute to them. So for our first woman, we’ve decided to tell the story of one of the greatest women swimmers in the sport with a life as fun and exciting as her name: Ms. Ethelda Bliebtrey.

Ethelda Bleibtrey was the USA’s first female Olympic swimming champion and the only person ever to win all the women’s swimming events at any Olympic Games. She took up competitive swimming for the first time in 1918, won the nationals within a year, and was the best in the world by the end of the second year (1920 Olympics).

Miss Bleibtrey won three gold medals in the Games at Antwerp and says only fate kept her from being swimming’s first four gold medal winner in one Olympic Game, an honor Hall of Famer Don Schollander accomplished 44 years later in Tokyo. “At that time,” she says, “I was the world record holder in backstroke but they didn’t have women’s backstroke, only freestyle in those Olympics.”

U.S. Girls 400 Freestyle Relay: Frances Schroth, Margaret Woodbridge, Ethelda Bliebtrey, Irene Guest

For her world and Olympic records in the 100 and 300 meter freestyle and anchor leg of the winning U.S. 400 freestyle relay, Ethelda was congratulated by King Albert of Belgium. She later surfed with the Prince of Wales in Hawaii, dated oarsman Jack Kelly in Atlantic City, and triumphantly toured the Panama Canal, Australia and New Zealand. The invitation down under came when she was the first girl ever to beat Hall of Famer Fanny Durack, the long-time Australian multi-world record holder on Fanny’s U.S. tour in 1919.

Miss Bleibtrey had several other firsts for which she got citations but no medals. Her first citation was for “nude swimming” at Manhattan Beach. She removed her stockings before going in to swim. This was considered nudity in 1919. Resulting publicity and public opinion swinging in her favor not only emancipated Ethelda from jail, but women’s swimming from stockings. On her trip to Australia with Charlotte Boyle the misses Bleibtrey and Boyle were the second and third famous women to bob their hair — something Irene Castle had just introduced. Charlotte’s parents told them not to come home until it grew out (citation #2), for which they were reprieved when the ship landed and the Boyle’s decided it didn’t look as bad as they had feared. Citation #3 got Ethelda arrested in Central Park and paddy-wagonned down to the New York police station for a night in jail but it also got New York its first big swimming pool in Central Park after Mayor Jimmy Walker intervened.

It happened like this: “The New York Daily News” wanted the City to open up its Central Park reservoir for swimming and arranged to have Ethelda arrested while diving in. For this they paid her $1,000.00, money she sorely needed after an abortive attempt to turn pro with a tank tour of the Keith Circuit. Her tank leaked — all over the theater — and Keith’s sued her instead of continuing her promised 14 week tour.

Ethelda and Charlotte Boyle with their Famed “bobbed” haircuts

Ethelda Bleibtrey, who started swimming because of polio, and took it up seriously to keep her friend Charlotte Boyle company, turned pro in 1922 after winning every national AAU championship from 50 yards to long distance (1920-1922) in an undefeated amateur career. She also started the U.S. Olympians Association with Jack Kelly, Sr., and later became a successful coach and swimming teacher in New York and Atlantic City. She is currently a practicing nurse in North Palm Beach, Florida — not as young but just as interesting. The sparkle remains in her eyes as she tells how they swam their 1920 Olympic races “in mud and not water,” in a tidal estuary; and how she participated in the first athletic sit-in when Hall of Famer Norman Ross organized the Olympic team to sit it out on the beach in Europe until the U.S. Olympic Committee sent better accommodations for the voyage home. “I have my memories,” says Ethelda, “and I guess some of those other people remember too. I owe a great deal to swimming and to Charlotte Boyle, who got me in swimming and L. deB. Handley, who coached me to the top.”

ISHOF salutes Black History Month: Remembering the Tennessee State Tigersharks

Left to Right, First Row: Captain Meldon Woods, Co-Captain Clyde Jame, Ronnie Webb, Jesse Dansby, Osborne Roy, Cornelias Shelby, Frank Oliver, James Bass and Roland Chatman. Second Row: Cecil Glenn, William Vaughn, Raymond Pierson, Robert Jenkins, George Haslarig, Leroy Brown, Frank Karsey, John Maxwell and Coach Thomas H. Hughes.

The Tennessee State University Tigersharks finished the 1960 – 61 swimming season with a 6 – 1 record, losing only to Indiana’s Ball State University, one of two white schools willing to swim TSU. The first time they met in the 1950s, TSU won. Co-captain Clyde James, was a finalist in the NAIA National Championships in the 100 yard butterfly. Clyde went on to become a legendary coach at the Brewster Recreation Center and Martin Luther King HS in Detroit. Tennessee State started its swimming team in 1945 and it’s coach, Thomas “Friend” Hughes was the first African American accepted as a member of the College Swimming Coaches Association in 1947.

Happy Birthday Steve Lundquist!!

Steve Lundquist (USA)

Honor Swimmer (1990)

FOR THE RECORD: OLYMPIC GAMES: 1984 gold (100m breaststroke; relay); U.S. NATIONALS: 14 (100yd, 200yd, 100m, 200m breaststroke; 200yd, 200m individual medley); NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS: 7 (100yd, 200yd breaststroke; 200yd individual medley); WORLD RECORDS: 9 (100m breaststroke; 200m individual medley; relays); PAN AMERICAN GAMES: 1979 gold (100m, 200m breaststroke; 1 relay); 1983 gold (100m, 200m breaststroke), bronze (200m individual medley; 1 relay); AMERICAN RECORD holder: (100yd, 200yd breaststroke); 1981, 1982 U.S. Swimmer of the Year; First swimmer in the world to break 2 minute barrier in the 200yd breaststroke.

“Lunk” the other swimmers called him except for the late Victor Davis who called him “the intimidator.” “It takes one to know one,” was Steve Lundquist’s reply. He was and is the golden boy of swimming, going right from the pool, medaling to modeling and a featured part on the afternoon “soap” “Search for Tomorrow”. He may have been a hot dog in the same sense as Johnny Weissmuller and Buster Crabbe. Steve was the first man in the world to break two minutes for the 200 yard breaststroke. “Lundquist can swim and win anything he wants to train for,” said Hall of Fame Honor Coach Walt Schlueter. He was almost as brilliant in the freestyle sprints and butterfly as he was in his breaststroke specialty. Steve was an honorary member of the 1980 Olympic Team. Unfortunately since the U.S. did not attend, Steve’s 100 meter breaststroke time, even though it was faster than the winning time, did not garnish him an Olympic gold. All totaled, he won two Olympic gold medals, set nine world records, won 14 U.S. Nationals, seven NCAA crowns and six gold medals in the Pan American Games. As an athlete in football, track, wrestling, water and snow skiing, tennis and especially swimming, he self-destructed on motorcycles and in dormitory wrestling matches, but that was only between races. In the pool he was always awesome. “Swimming World” magazine picked him as 1981 and 1982 World Swimmer of the Year. To all of this, Weissmuller and Crabbe might add, “Yes, old Steve is a pretty fair country swimmer.” The “country is Lake Spivey of Jonesboro, Georgia, USA where the Lunk was born in 1961.

Black History Month: Despite Stolen Gold, Enith Brigitha Was a Sporting Pioneer

By John Lohn, Editor, Swimming World

Emerging as a youth star from the island nation of Curacao in the Netherlands Antilles, Brigitha etched herself as one of the world’s most consistent performers during the 1970s, appearing in a pair of Olympic Games and three versions of the World Championships. More, she was a regular medalist at the European Championships.

It didn’t take long for Brigitha to become a known entity in the pool, such was her talent in the freestyle and backstroke events. But there was another factor that made the Dutchwoman impossible to miss. On a deck filled with white athletes, Brigitha stood out as one of the few members of her race to step onto a starting block, let alone contend with the world’s best.

In Montreal in 1976, Brigitha captured bronze medals in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle to become the first black swimmer to stand on the podium at the Olympic Games. The efforts delivered a breakthrough for racial diversity in the sport and arrived 12 years ahead of Anthony Nesty’s historic performance. It was at the 1988 Games in Seoul in which Nesty, from Suriname, edged American Matt Biondi by .01 for gold in the 100 butterfly.

Photo courtesy: Enith Brigitha

What Brigitha achieved in Montreal fit neatly with the progression she showed in the preceding years. After advancing to the finals of three events at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, Brigitha was a medalist in her next five international competitions. It was this consistency that eventually led to Brigitha’s 2015 induction into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

“(It meant a lot) to be told by a coach, ‘We believe in you. You are going to reach the top,’” Brigitha said during her induction speech into the Hall of Fame. “It is so important that people express trust in you and your qualities when you are working on your career. I am very grateful to all the people who were there for me when I needed them the most.”

Photo Courtesy: Enith Brigitha

Brigitha’s first medals in international competition were claimed at the inaugural World Championships. In Belgrade, Yugoslavia, Brigitha earned a silver medal in the 200 backstroke and added a bronze medal in the 100 freestyle. That performance was followed a year later by a five-medal haul at the European Championships, with four of those medals earned in individual action. Aside from winning a silver medal in the 200 freestyle, Brigitha collected bronze medals in the 100 freestyle and both backstroke events.

Bronze medals were added at the 1975 World Championships in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle and carried Brigitha into her second Olympiad. A silver medal in the 100 freestyle marked her lone individual podium finish at the 1977 European Championships, while the 1978 World Champs did not yield a medal and led the Dutch star into retirement.

Shirley Babashoff Kornelia Ender and Enith Brigitha 1973 – Photo Courtesy – NT/CLArchive

Despite her success, which twice led to Brigitha being named the Netherlands’ Athlete of the Year, her career is also defined by what could have been. No two athletes were more wronged by East Germany’s systematic doping program than Brigitha and the United States’ Shirley Babashoff. At the 1976 Olympics, Babashoff won silver medals behind East Germans in three events, prompting the American to accuse – accurately, it was eventually proved – her East German rivals of steroid use. For her willingness to speak out, Babashoff was vilified in the press, called a sore loser and tagged with the nickname, “Surly Shirley.”

Brigitha experienced similar misfortune while racing against the East German machine. Of the 11 individual medals won by the Dutchwoman in international action, she was beaten by at least one swimmer from the German Democratic Republic in 10 of those events. Her bronze medal in the 100 freestyle is the performance that stands out.

In the final of the 100 free in Montreal, Brigitha placed behind East Germany’s Kornelia Ender and Petra Priemer. Upon the fall of the Berlin Wall and the release of thousands of documents of the East German Secret Police, known as the Stasi, it was revealed that Ender and Priemer were part of a systematic-doping program that spanned the early 1970s into the late 1980s and provided countless East German athletes with enhanced support, primarily in the form of the anabolic steroid, Oral-Turinabol.

Had Ender and Priemer not been steroid-fueled foes or been disqualified for their use of performance-enhancing drugs, Brigitha would have been the first black swimmer to win an Olympic gold medal, and her Hall of Fame induction would have come much earlier. Ender was a particular hurdle for Brigitha, as she won gold medals in six of the events in which Brigitha medaled on the international stage.

“Some gold medals didn’t come my way for reasons that are now well-known, namely the use of drugs by my rivals,” Brigitha said. “That gold has come my way (through induction into) the Hall of Fame. I thank the women who set an example and those who crossed the line with confidence and respect, but without the use of drugs.”

Babashoff has been a vocal proponent of reallocation, citing the need to right a confirmed wrong. If nothing else, she has sought recognition from the IOC and FINA that an illicit program was at work and damaged careers. Those pleas, however, have fallen short of triggering change, the IOC unwilling to edit the record book.

Calls have frequently been made for East German medals – Olympic, World Championships and European Champs – to be stripped and reallocated to the athletes who followed in the official results. However, officials from the International Olympic Committee and FINA, swimming’s global governing body, have refused to meet these demands.

“Every once in a while, we’ve looked at the issue hypothetically,” once stated Canadian Dick Pound, a 1960 Olympic swimmer and former Vice President of the International Olympic Committee. “But it’s just a nightmare when you try to rejigger what you think might have been history. For the IOC to step in and make these God-like decisions as to who should have gotten what…It’s just a bottomless swamp.”

Even without an Olympic gold medal that can be considered her right, Brigitha shines as a pioneer. In a sport in which black athletes were rare participants, Brigitha compiled an exquisite portfolio and proudly carried her race to heights that had never before been realized.

Happy Birthday Rowdy Gaines !!!

Rowdy Gaines (USA) 1995 Honor Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: 1984 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (100m freestyle, 4x100m medley relay, 4x100m freestyle relay); 8 WORLD RECORDS: (1-100m freestyle, 2-200m freestyle, 2-4x100m freestyle relay, 3-4x100m medley relay); 1978 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (4x100m freestyle relay, 4x200m freestyle relay), silver (200m freestyle); 1982 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (4x100m medley relay, 4x100m freestyle relay), silver (100m, 200m freestyle); 1979 PAN AMERICAN GAMES: gold (200m freestyle, 4x100m freestyle relay, 4x200m freestyle relay); 1983 PAN AMERICAN GAMES: gold (100m freestyle, 4x100m freestyle relay, 4x100m medley relay, 4x200m freestyle relay), bronze (200m freestyle); 17 U.S. NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: 9 Outdoor, 8 Indoor; 8 NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS: 50 yd, 100yd, 200yd freestyle; 400m, 800m freestyle relays.

Rowdy Gaines was named after the rambunctious western her in the television series “Rawhide.” He is described by his merits for being “rapidly successful, competitive, and very, very fast” and feels more at home in the water than on land. He has broken eight world records and continues to swim today.

Rowdy loved the water as a child, but did not begin his notorious swimming career until the late age of 17 with a 16th place finish in the Florida High School Championship. The following year, Rowdy came back to win the State championships and quickly developed into a world class contender when he placed second in the 200m freestyle at the World Championships in 1989. Rowdy was recruited to Auburn University where he stroked to American records in the 100 and 200 yard freestyles and to the world record in the 200m freestyle in 1:49.16. By 1980, he was named “World Swimmer of the Year.”

It was at the pinnacle of his swimming career that he suffered a tremendous disappointment when the 1980 US Olympic Team boycotted the Olympic Games. Shortly thereafter, he retired, only to return with a vengeance a year and a half later, determined to regain his place in the swimming world and claim the medals he was unable to obtain in 1980.

Rowdy had no problem grasping three Olympic gold medals amidst roaring fans who believed in the “old man” of the 1984 Olympics. Rowdy’s crowning moments of capturing gold by winning the 100m freestyle and the 4×100 medley and freestyle relays will remain sacred to him and his fans.

Throughout his memorable career, Rowdy won three Olympic gold medals, set eight world records, won seven World Championship medals, not to mention numerous medals in the Pan American Games, US National Championships, and NCAA Championships.

Since his retirement, Rowdy has been asked to endorse many products, has been a swimming commentator for CNN, ABC, and NBC, and has written articles for the FINA Swimming and Diving Magazine. Today, Rowdy lives in Hawaii with his wife Judy and their three children. He manages a health and fitness center, coaches swimming and continues to feel at home in the water swimming in a Masters program.

Happy Birthday Kenneth Treadway!!

Kenneth Treadway (USA)

Honor Contributor (1983)

Having been born in Oklahoma during the 1930’s into a Cherokee Indian Sharecropper family may cause one to ask, “How in the world did this guy become an inductee into the International Swimming Hall of Fame?” Buck Dawson would have answered that question by telling you, “He’s just a good ol’ country boy who loves people and swimming”.

Ken Treadway has received almost every award our sport has to offer, from receiving the AAU “Neptune” award in 1972, then swimming’s highest honor, to being inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1983. Ken doesn’t need another award, in fact he recently donated some of the ones he did receive to ISHOF. But he does deserve to be remembered for all he has done for swimming. Because Ken and his wife Bettie don’t travel much anymore, Buck Dawson believed the Olympic Trials in Omaha, just a three hour drive from their home in Overland Park, Kansas, provided swimming with an opportunity to recognize and once again thank Ken for all he has done for swimming.

Over a span of 45 years Ken Treadway was a competitor, coach, official, chairman of state, national and Olympic Committees as well as an employee of the Phillips Petroleum Company. He founded the Phillips 66 Splash Club, in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, in 1950 and the team is still one of the most successful swimming organizations in history. He then went on to found the successful Phillips 66 Long Beach Aquatic Club with Coach Don Gambril.

He persuaded his company to sponsor an annual swim meet and in 1963 this led to Phillips’ hosting four national swimming championships. In 1972, Ken and Dr. John Bogert, another “Red Man,” developed a plan to become a National Sponsor of Swimming. The sponsorship started in 1973 and today ConocoPhillips’ sponsorship of USA Swimming is the longest continuous corporate sponsorship of any amateur sport in America.

It was Ken and the late Dr. Hal Henning who had the honor of representing the United States at the FINA meeting when the International Swimming Hall of Fame was approved by that international body of aquatics.

Coach Peter Daland can tell stories all night about his and Ken’s travels around the world in support of a program Ken started called “Coaching The Coaches”. Both of them were great international ambassadors for the country, for ISHOF, for the American Swimming Coaches Association, for AAU Swimming and their sponsor, ConocoPhillips. In fact one of their sojourns was requested by the U. S. Department of State!

Treadway’s ability to get right at the crux of a problem, and then lead parties to an effective diplomatic compromise, endeared him to the swimming world, created advancement for him at Phillips and led to his selection as a member of the U.S. Olympic Swimming Team’s Staff in Tokyo, Mexico City and Munich.

Not the least of his accomplishments was finding a pathway for swimming and diving to operate in a high level business- like manner and to enhance their image without “passing the plate” at swim meets.

In 1983, he was inducted into the ISHOF as an Honoree Contributor, and now, we take time to remember and honor him again with ISHOF’s President’s Award.

Black History Month: During General Slocum Disaster, Harry George Was a Hero

Story by ISHOF Curator, Bruce Wigo

Black History Month: During General Slocum Disaster, Harry George Was a Hero

The General Slocum steamship disaster was the greatest single catastrophe in New York City’s history until Sept. 11 terrorist attacks in 2001. On June 15, 1904, the Gen. Slocum was taking a group of almost 1,400 passengers, mostly women and children, on a trip of New York City’s East River to a picnic on Long Island.

Photo Courtesy: Pittsburgh Courier

The ship caught fire shortly after leaving the dock. Most of the passengers tried to escape the fire by jumping into the water, and because they didn’t know how to swim, they drowned. Bodies of mothers, grandmothers, and girls washed up on the shorelines for days. One of the forgotten heroes, saving some of the passengers, was Harry N. George, an African American.

321.9K

Did you grow up wanting to be a mermaid Make your childhood dream a reality thanks to this course

George was credited with saving 23 lives through his courage and resolve and was presented the Congressional Medal of Honor. He was also awarded the Life-Saving Gold Medal of New York.

The lesson from the Slocum disaster wasn’t lost on the nation: “Learn to swim!” commanded an editorial in the New York Herald that was repeated throughout the country. “That should be the resolve of every intelligent woman who does not already know how, upon reading the pitiful story of how woman after woman drowned within just a few feet of shore.”

As a consequence of the Slocum disaster, the American Red Cross was moved to begin its water safety and lifesaving programs and swimming became an essential part of public education. Unfortunately, most African Americans were denied the same opportunities to learn to swim, as virtually all pools and beaches were closed to non-whites during the first half of the 20th Century, in spite of the heroics of Harry N. George. It would not be until the 1930s when the first African Americans were certified as Red Cross Water Safety instructors and Lifeguards.

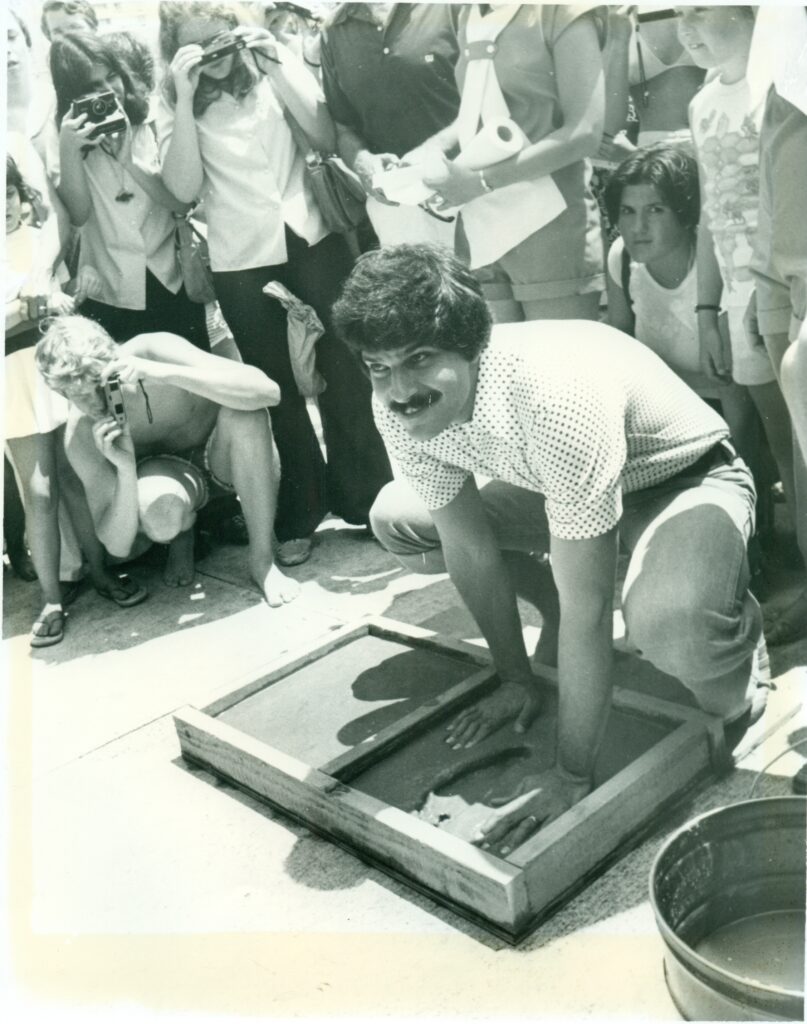

Happy Birthday Mark Spitz!!!

MARK SPITZ (USA) 1977 Honor Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: OLYMPIC GAMES: 1968 gold (4x100m, 4x200m freestyle relay), silver (100m butterfly), bronze (100m freestyle); 1972 gold (100m, 200m freestyle; 100m, 200m butterfly; 4x100m, 4x200m freestyle relay; 4x100m medley relay); PAN AMERICAN GAMES: 1967 (5 gold); WORLD RECORDS: 33; NATIONAL AAU CHAMPIONSHIPS: 24; AMERICAN RECORDS: 38; NCAA Titles: 8; 1972 “World Swimmer of the Year”.

Mark Spitz was the 1971 Sullivan Award winner as the AAU’s top athlete in any sport, an omen of things to come. His 7 gold medals in the 1972 Olympics are all the more remarkable in that all were World Records. They were in such varied distances as the sprint 100m Freestyle and the endurance 200m Butterfly. He was everybody’s World Athlete of the Year for 1972 and along with Johnny Weissmuller is rated one of the greatest swimmers the world has ever known. This remarkable consistency was not easily come by. Always brilliant he ranged from the World’s best 10-and-under to the most disappointing swimmer at the 1968 Olympics before sticking it to his critics once and for all in Munich. Spitz was fortunate to have three of the greatest swim coaches the United States has known — Hall of Famers Sherm Chavoor, Doc Counsilman and George Haines.

ISHOF Honors Black History Month with 2012 Gold Medallion Recipient: Superstar Milton Gray Campbell ~ Read his story!

Story by ISHOF Curator, Bruce Wigo

In 2016, Richard “Sonny” Tanabe, the legendary Hawaiian spear fisherman, author, member of the 1956 U.S. Olympic swimming team and Indiana University great stopped by the Hall of Fame with his wife Vicki and took a tour of the museum. “I always wondered why there weren’t more black swimmers,” Sonny told me, after reviewing our Black swimming history exhibit. “But I knew an African-American who was an All-American swimmer back in 1951.”

That swimmer was Milton Campbell. In 1953, as an eighteen year old, Milt was named by Sport Magazine as the best H.S. athlete in the world and it’s hard to imagine any high schooler on the planet who has ever had a superior claim to that title. As a junior, not only had Campbell won the silver medal in the decathlon at the 1952 Olympic Games, but he had also finished fifth in the open high hurdles at the U.S. trials. He scored 180 points for his high school’s football team in one season and subbing once for a sick heavyweight wrestler, he took only a minute and a half to pin the boy who would go on to be state champion. On top of that, he was an All-America swimmer. After high school, Campbell went on to star in both football and track at Indiana University, won a few national titles in the high hurdles and capped his amateur career by winning the gold medal in the decathlon at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia.

Sonny Tanabe learned about Milt’s swimming skills in the fall of 1953 when both were freshmen at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. One day, when Sonny was swimming some laps with his teammate, fellow Hawaiian and future Olympic swimmer Bill Woolsey, Milt Campbell walked into the natatorium.

“When Milt saw us he walked across the pool and jumped into the lane next to me,” recalled Sonny.“He knew Bill and me because we had some classes together and he asked if he could swim a few laps with us. ‘Sure,’ we both said. You didn’t see any black swimmers in those days, so we weren’t sure if he was joking or not. Anyway, I told him we were going to do a couple of 50’s and he said ‘OK.’ On my ‘go’ the three of us pushed off the wall and to our amazement Milt was right there with us at the 25. ‘Wow! I mean here were two future Olympic swimmers and he was matching us stroke for stroke. ‘You’re a damn good swimmer,’ I told Milt when we finished. That’s when he told us he had been an All-American swimmer in high school.”

Amazing! When I told Sonny I’d like to talk to Milt, he said he’d track him down. True to his word, he emailed me Milt’s numberand here’s the story as told to me by Milt Campbell, in his own words.

“I got interested in swimming when I was a freshman at Plainfield H.S. in New Jersey. I had just finished playing J.V. football and we had an undefeated season. My brother Tom was a junior and a three-sport star in football, basketball and track. He was the star running back for the varsity; I was the star running back for the J.V. squad. Everybody was always comparing me to Tom. While that was flattering I wantedto step out of his shadow and find my own identity. So after football season, I was determined to do something other than basketball. My plan was to see what the other sports had to offer. I had some friends on the wrestling team, so I knew what that was like, so my first stop was to check out the swim team. I knew how to swim because when I was young my dad would take our family out to a canal. He’d swim across, back and forth while my brother and I played in the shallow water. I remember my dad taking us once to the community pool. There weren’t any laws preventing us from being there, like in the south, but it was clear we weren’t welcome. That’s why we went swimming with other black folks in the canals and rivers. Anyway, it wasn’t until I was a little older and went to summer camp that I learned to swim. I learned from watching the older boys and when I tried to imitate them, they would encourage me by moving their arms and yelling, ‘Stroke your arms! Stroke your arms!’ I was a good copycat and that’s how I learned to swim. So, there I was sitting in the stands when one of the swimmers, a white boy, comes up to me and asks me what I’m doing in the pool. ‘I’m thinking about joining the swim team,’ I replied.

‘We’ve never had a colored boy swim for us,’ he said. ‘I don’t think you can swim.’ I asked him why he thought that. He said, ‘because all the waters in Africa are infested with crocodiles so your people never took to the water.’ I looked athim and said, ‘what the hell does that have to do with me? I was born in Plainfield.’ I’m not African, I thought to myself. There aren’t any crocodiles in the waters of New Jersey. What did hemean, ‘your people?’ My father knew how to swim and so did I. Whenever someone has told me I can’t do something, it has become my mission in life to prove them wrong. That has always been my strongest motivation. It’s a concept I now lecture on: It’s not important what you say to me, it’s important what I say to me.

Anyway, as the boy walked away and these thoughts were racingthrough my mind, the coach walked over to where I was sitting. Coach Victor Liske was, at 40 years of age, in the prime of his Hall of Fame coaching career that ended in 1966 with a record of 266 wins, 84 losses, 2 ties and 5 undefeated seasons. As a kid he had lost a couple of fingers and most of his left leg in a train wreck. He walked with a noticeable limp because of his prosthesis. But that didn’t hold him back. He played baseball and was a record setting backstroker in high school and was captain of Lafayette College’s swim team for the 1932-33 season.

What brought me into the pool? he asked. I told him I was thinking about joining the swim team.

‘That’s great!’ he said. ‘You’ve got big hands, big feet – you’re a great athlete – you’ll make a great swimmer!’ And I could tell hemeant it. ‘What event do you think you’d like to swim?’ he asked.

Well, I’d never seen a meet so I was kind of at a loss for words. Then it hit me. ‘You know that boy I was just talking with?” Coach nodded. ‘What does he swim?’ ‘Sprint freestyle. He’s our top sprinter.’ ‘Sprint freestyle! That’s what I want to do,’ I said. Now when I say I knewhow to swim, I did know how, but not very well. I swam with my head out and knew nothing about racing techniques, or starts and turns. But Coach Liske saw my potential and worked with me. I remember he had me do a lot of drills with a board. Progress was slow at first, but he was a good, patient teacher and I was a quick learner.

Our pool at Plainfield was shallow at one end and deep at the other. Sometimes after practice coach would bring out a ball and we’d play water polo. I was pretty big in comparison to the other boys, even as a freshman, and was pretty much unstoppable in the shallow end. Everyone would jump on me; sometimes even my own teammates would jump on me and try to pry the ball out of my grasp. It was really great fun. Finally they figured out the only way to get the ball out of my hands was to drag me to the deep end and hold me under water. I was afraid and panicked when I got dunked and didn’t have my feet on the bottom, so I’d let go of the ball. This goes back to an incident when I little. A kid jumped on my back in a canal and I almost drowned. Coach saw the panic on my face and a few days later told me stay after practice.

Coach Liske was totally unselfconscious about taking off and putting on his prosthetic legs. While I waited, Coach got changed and put on his peg leg and joined me at the edge of the deep end. ‘Get in,’ he said, jumping in after me. When we got out into the middle of the pool he told me to dunk him. ‘Go ahead, dunk me!’ So I dunked him! ‘No, really, tackle and dunk me like we’re in a water polo game.’ So I tackled him, held him under and then shoved him to the bottom of the pool. When he came up twenty feet away from me, he explained that when I dunked him he just held his breath, relaxed and went down to the bottom. Then he pushed off and returned to the surface. ‘Don’t fight, they’re going to sink you,’ he said. ‘Find another solution to the problem.’ It was his way of teaching me about life through sports. Funny thing, after I learned to be comfortable when tackled in the deep water, the team stopped asking to play polo.

At the end of my first year swimming I was second to that boy who didn’t think I’d make the team. But the next year I broke all his records. Our team went undefeated and I swam the anchor leg on Plainfield’s All-American medley relay that won the Eastern Championship. I didn’t swim my junior year because I was preparing for the Olympics trials and my senior year I was focused on getting a scholarship for football and track, so there was no time to swim again.

Sounds like you had a great experience with Coach Liske. Can you tell me more about him?

He was like a guardian angel to me. A fantastic man and I loved him dearly. I felt pretty much the same way about my track coach, Harold Brugiere. I was really blessed by having these two mentors. It’s funny I would feel that way, because I remember when I was young my dad told us to be careful around white men – that we shouldn’t trust them.

I never heard Mr. Liske berate or speak badly of anyone, but if you messed up, he made sure you learned a lesson. Here’s one example of what I’m talking about. I had a lot of friends on the wrestling team and after swim practice I would wander into the wrestling room and fool around, wrestle with the guys. One day, the wrestling team had a match against Jefferson High. It was a big match. I wanted to see it so bad that I told Mr. Liske I was sick and couldn’t swim that day. He said ‘OK, go home and get some rest and I’ll see you tomorrow.’ Instead of going home, I went up through a back stairwell and entered a back door to the gymnasium so I could watch the match. I was near the locker room and when the door opened I could see our heavyweight throwing up. When coach Rosy came out I asked him what was the matter. ‘Oh, he’s just nervous. He’ll get over it,’ he said. ‘Well, if he doesn’t get over it and you need me, I’ll do it,’ I told him. ‘Thanks Milt, but you’d get hurt. This Jefferson guy’s a killer. One of the best in the state.’ Well, as it looked like the match was going to down to the last weight class, the coaches were talking about forfeiting the heavyweight class because guy’s problem was more than nerves,he was really sick. So the assistant coach starts in on coach Rosy. “Milt’s strong as an ox and I’ve seen him wrestle with the boys after our practice. What have we got to lose?’ Finally, Rosy relented, ‘Ok, get him dressed.” Well, I pinned the guy in one minute and 28 seconds and Plainfield won the match. That guy went on to win the state title by the way. When I got to school the next day, I was a hero. Everybody was congratulating me in the hallways on the way to my first class – which was math with Mr. Liske. Unlike everyone else in the school, Mr. Liske wasn’t happy to see me. As we took our seats and got out our books, he sternly said: ‘put your books away! It has come to my attention that we have a liar in our midst.’ He then proceeded to lecture us on the virtue of honesty in a way that I felt obligated to apologize to him before the whole class. I never felt so bad. Here was a guy who had been so good to me and I lied to him. When the bell rang to dismiss the class, I couldn’t wait to get out of that room, but Mr. Liske called me over. Oh No! Not more, I thought. But instead of being mad, he patted me on the back and said, “great job!” I was forgiven andat swim practice that afternoon all was well again!

I stayed in contact with Coach Liske over the years and when he was in failing health in 2008 I visited him often and he would cry every time he’d see me. I told him if he kept crying I wasn’t go- ing to visit him any more. ‘You don’t need to cry when you see me,’ I said. ‘Think about the good times we had.’ ‘That’s why I’m crying,” he said. On one of my last visits before he passed away at the age of 98, we had a good laugh over the time we beat the Army Plebes 40 -35, by winning the last relay on which I was the anchor and came from behind to win the race. We sang on the bus all the way home, from the time we left West Point to the time we pulled into the high school parking lot. It was one of those days you, your team and your coach never forget.

We talked a little about why more African Americans aren’t swimming and Milt understands the problem. It’s all in the mind. We have to change people’s mental attitude. I had the example of my father who was a good swimmer and then I had coaches who helped me to believe anything was possible.

As the greatest athlete of his generation, I wondered why Milt didn’t receive the same commercial success and public recognition as otherGold Medal decathletes that went before or after him. Milt wasn’t movie star handsome like Bob Mathias or Rafer Johnson, but I believe, like many social historians, that it was because America wasn’t ready for black man to have the title of the World’s Greatest Athlete. Add that to the fact that he married a white woman at a time when half of the states had anti-miscegenation laws and you can see why Milton Campbell is aforgotten hero.

I can only imagine what kind of swimmer or water polo player Milt Campbell might have been, or the impact he might have made on our culture and the widely accepted stereotype that “blacks can’t swim” had he continued swimming. Listening to Sonny Tanabe and Milt tell their stories, and reading what coach Liske told people for over fifty years, I’m convinced that if Milt stuck with swimming he could have been an Olympic Champion in our sport too!

Friends we’ve lost in 2024

Dr. Ron O’Brien – November 19, 2024

The Sport of Diving loses a Legend: Dr. Ron O’Brien dies at age 86 at home in Naples, Florida

Casey Converse – August 10, 2024

Passages: The Gift of Casey Converse; Distance Legend Passes Away at 66

Paul W. “Buddy” Bucha July 31st, 2024

Passings: ISHOF loses 1997 Gold Medallion Recipient, Paul W. “Buddy” Bucha ~ longtime ISHOF friend

Carolyn Schuler Jones – July 22, 2024

Passages: Carolyn Schuler Jones, Two-Time Olympic Gold Medalist Dies at 81

Brent Rutemiller – June 17, 2024

David Wilkie – May 22, 2024

Great Britain and the ISHOF family lose a great one: David Wilkie loses his battle with cancer…..

Jon Urbanchek – May 9, 2024

Passages: ISHOF Honor Coach Jon Urbanchek, Iconic Olympic, Michigan Coach Dies; Legacy Will Endure

Judith McGowan – March 10, 2024

Giuseppe D’Altrui – February 22, 2024

The world of water polo loses a great: Giuseppe D’Altrui

Eddie Sinnott – February 20, 2024

Lance Larson – January 19, 2024

Passages: Lance Larson, 1980 ISHOF Honoree Controversially Denied Olympic Gold, Dies at 83