Happy Birthday Ted Stickles !!!

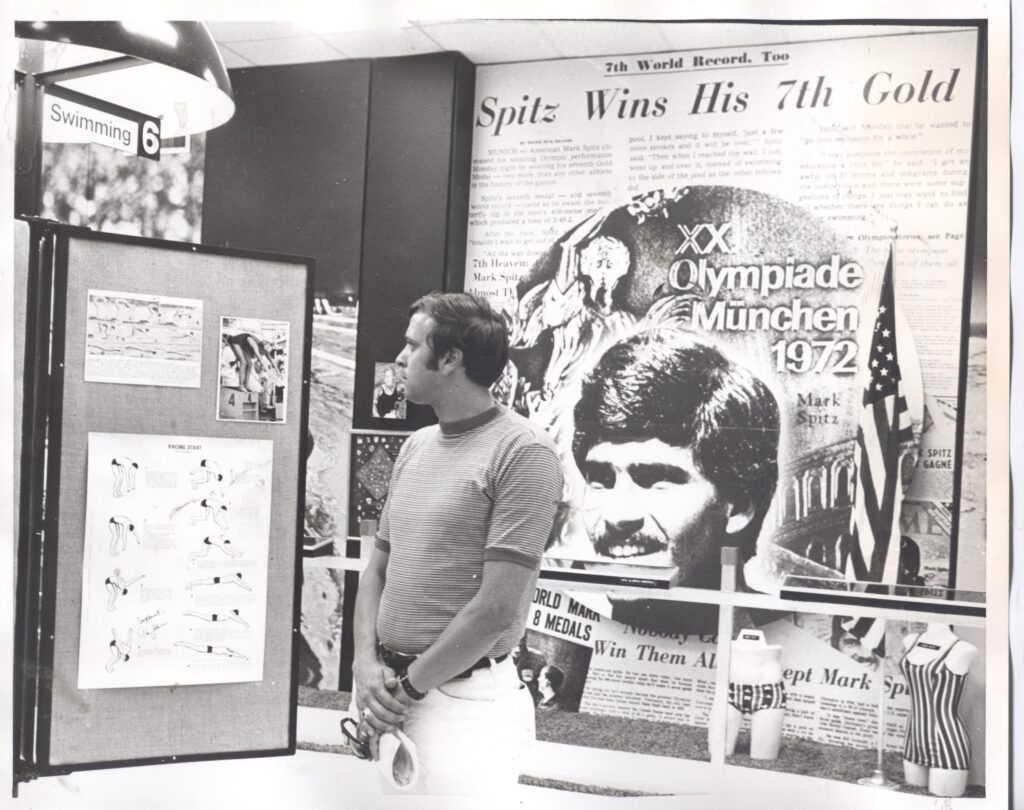

EDWARD “TED” STICKLES (USA) 1995 Honor Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: 4 WORLD RECORDS: 400m individual medley; 8 U.S. NATIONAL AAU CHAMPIONSHIPS: 200m individual medley, 400m individual medley.

Ted Stickles swam with Doc Councilman’s legendary Indiana University swim team from 1962-1965. At on point during his career, he and his roommate, Hall of Famer Chet Jastremski, held a total of seven world records. Ted dominated the individual medley throughout the early ’60s, breaking a total of nine world records throughout his career.

His mother taught him to swim at an early age, but it was not until he entered high school that Ted began competitive swimming. After enjoying a successful high school career, Hall of Famer Doc Councilman recruited him to his IU team.

At first, Ted felt that Doc had made a mistake in his recruitment, but before long, he surprised himself and began to break unforgettable records. Ted was one of the first people to actually train for the individual medley events. Ted’s ease in moving from one stroke to another and fluidity without breaking stroke helped him be the first person to break two minutes in the 200 yard individual medley and five minutes in the 400 meter individual medley. For a span of three years, Ted Stickles held all of the world records in the individual medley events.

At the height of his career, he developed tendonitis in his elbow, hindering his ability to train. Yet Ted continued to swim and barely missed making the ’64 Olympic team. This was a disappointment because his sister, Terri Stickles, made the team; they would have been the first brother and sister to make an Olympic team.

Ted went on to coach swimming for the University of Illinois and Louisiana State University. Presently, he resides in Louisiana with his wife and two children and is event management director for all athletic functions at Louisiana State University.

Hook’ Em: Texas Captures 16th National Title Behind Hubert Kos, 2023 ISHOF Honoree Bob Bowman and Reassembled Roster

Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

A win in the 200 medley relay started out the Longhorns’ national-title run.

by David Rieder – Senior Writer

30 March 2025

Hook’ Em: Texas Captures 16th National Title Behind Hubert Kos, 2023 ISHOF Honoree Bob Bowman and Reassembled Roster

A seventh-place finish at last year’s NCAA Men’s Championships was a highly unusual result for a University of Texas team so accustomed to finishing atop the table.

During the four decades in which Eddie Reese helmed the program, Texas won 15 national titles, the most all-time by a single swimming program (men’s or women’s) and by a single coach. For 15 consecutive national meets from 2008 through 2023, Texas finished in the top three, and it would have been 16 if not for the cancellation of the 2020 meet by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The 2024 season was an aberration, Reese having already announced his retirement (for the second time) and the program’s future uncertain. Less than 48 hours later, the team announced Bob Bowman would take over, and he would put together a title-winning squad in his first year.

“I’m really proud of this team because they didn’t know me, I didn’t know them. It was a little rocky at first trying to figure everything out,” Bowman said. “I remember in our first team meeting saying that we could contend for a championship. In here, I was like, ‘Maybe next year.’ But then they started getting better and we started swimming some meets and I started seeing some things. We were able to get our roster together a little bit with some firepower. It’s really kind of gratifying to all of those efforts came together, but it’s really all about those guys and their hard work.”

The Longhorns finished this year’s NCAA Championships with 490 points, edging out California by just 19 points. The margin was tiny but actually greater than in Texas’ two previous national wins. Previously, the team won by 17 points in 2021 and by 11.5 points in 2018, with the Golden Bears finishing second on both occasions.

Cal placed second with 471 points, with Indiana’s spirited effort resulting in a third-place finish with 459 points. Florida was fourth (315) while Tennessee grabbed fifth (266.5) thanks to exceptional results in the sprint events. Defending champion Arizona State took sixth (248), followed by Georgia (238.5), Stanford (216), NC State (178) and Virginia Tech (107.5).

When Bowman took over the Texas men’s program, he was coming off putting together the most unlikely of national championship teams in men’s swimming history. Bowman came to Texas after nine years at Arizona State, a program that had been cut and resurrected a decade and a half earlier. During his time in Tempe, the coach lifted the Sun Devils from conference also-ran to national champs. Leon Marchand blossomed into a superstar and eventual Olympic hero under Bowman, and the Frenchman was the catalyst in a 79-point win over Cal.

Hubert Kos — Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

At his next stop, the Hall-of-Fame coach would no longer have the talents of Marchand, now a professional. Only one swimmer from the ASU diaspora joined him in Austin, though it was World and eventual Olympic champion Hubert Kos, who would flourish in his first year racing for Texas, surging to three national titles after never finishing higher than second with the Sun Devils. Kos capped off his meet with a record-crushing performance in the 200 backstroke.

“Obviously it’s two different feelings, but at the end of the day, it’s kind of the same,” Kos said. “Winning is winning, and that’s why we do this sport, to win at the end of the day. So really, really happy with how this meet turned out and so happy for all the guys, because they put in all the hard work. Bob made us put in all this hard work. So really happy to see it come through at the end.”

Of course, building a championship team requires contributions from all angles. Kos was not lifting Texas back to the promised land by himself. The modern era of college swimming requires coaches to explore every option for their programs, and Bowman took full advantage, with returning swimmers, transfers, divers and freshmen all contributing.

Reese’s successor would inherit building blocks. Luke Hobson won a national title in the 200 free and became the fastest swimmer ever in the event. A freshman class featuring Will Modglin and Nate Germonprez had shown promise. Rex Maurer transferred in from Stanford, and after an up-and-down freshman season, became a star at Texas, culminating national titles in the 500 free and 400 IM and a runnerup finish in the 1650 free. Also joining was Chris Guiliano, who became the first American man since Matt Biondi to race the 50, 100 and 200-meter events at the Olympic Games.

Guiliano was a college home following the suspension of the Notre Dame men’s program for the season, and he chose to spend the spring semester racing for Texas. It may have been the addition of Guiliano that took Texas from great team to true contender as Guiliano’s presence was critical for Texas finishing first, second, second, sixth and seventh in the relays.

Hobson remained a star, lowering his American and NCAA records in the 200 free while finishing second in the 500 free and tied for ninth in the 100 free, and he also provided Bowman a valuable bridge from the previous era of Texas swimming. “Luke’s the quiet leader of the team,” Bowman said. “Not very outspoken, but he does everything right. He lives the right way, he trains the right way, he behaves the right way. He’s been invaluable. Also to teach me about Texas culture. It’s been important to make a smooth transition.”

As for the other returners, Modglin qualified for three A-finals while Germonprez became one of the top breaststrokers in the country, taking third in the 100 breast and ninth over 200 yards. Fellow sophomores Camden Taylor and Will Scholtz made one B-final apiece.

Texas also had two fifth-year swimmers on the team who were part of Reese’s last championship team in 2021: David Johnston, who returned to the team after a redshirt year, and Coby Carrozza, a 200 freestyle veteran who was part of this year’s Texas group that smashed the American record and finished just behind Cal’s historic sub-6:00 effort. Divers Jacob Welsh and Nicholas Harris scored points while freshman Cooper Lucas qualified for two evening swims, topping out with a sixth-place finish in the 400 IM.

Those performances allowed Texas to narrowly take down Cal and Indiana, winning the program’s 16th title in the first year under Bowman. Sure, rebuilding a national contender at Texas was never going to be as challenging as what Bowman accomplished at Arizona State, but no one could have expected it to happen in 12 months. This latest roster, assembled considering the new realities of college swimming, has restored the Longhorns’ dynasty.

NCAA Division I Men’s Championships Meet Page

Men – Team Rankings – Through Event 21

1. Texas 490 2. California 471

3. Indiana 459 4. Florida 315

5. Tennessee 266.5 6. Arizona St 248

7. Georgia 238.5 8. Stanford 216

9. NC State 178 10. Virginia Tech 107.5

11. Michigan 98.5 12. Texas A&M 95.5

13. Alabama 93 14. Louisville 84

15. Southern Cal 80 16. Ohio St 78

17. Purdue 62 18. Florida St 54

19. Lsu 47 20. Yale 30

20. Kentucky 30 22. Wisconsin 28

23. Miami (Fl) 25 23. UNC 25

25. Georgia Tech 24 26. Brown 22

27. Penn 17 28. Minnesota 16

29. Arizona 15.5 30. Army 15

30. University of Utah 15 32. Auburn 14

32. Virginia 14 34. Pittsburgh 13

35. Smu 12 36. Missouri 10

37. Cornell 6 38. Cal Baptist 4

39. South Carolina 1

Happy Birthday Tom Stock!!

Tom Stock (USA)

Honor Swimmer (1989)

The information on this page was written the year of their induction.

FOR THE RECORD: WORLD RECORDS: 10 (100m, 200m, 220yd backstroke; relays); AAU NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: 11 (100m, 200m, 220yd backstroke; relays; AMERICAN RECORDS: 14 (200yd, 220 yd, 100m, 200m backstroke; relays).

Tom Stock may just be the greatest backstroker who never swam in the Olympics, due to prolonged illness before the 1964 Olympic Games. He may have been the smallest backstroker to hold a world record. He weighed in at 130 lbs. and set 10 world records. When he was in his second month of competition at Indiana University, Stock became the first man in history to swim the 200 yard backstroke under 2 minutes. This was a performance that caused his coach, “Doc” Counsilman to put a sign on the locker room door which said, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, but the size of the fight in the dog.”

This desire and an amazing feel of the water, long arms and a powerful kick, made Tom Stock great in the opinion of his famous coach. To the spectators he looked like he was riding on top of the water from the waist up. This unique buoyancy, plus the fastest arm turnover yet seen in backstroke, took him to 11 National championships, 14 American records and five world records in the 100 meter, 200 meter, 110 yard, 220 yard backstroke and the 400 meter medley relay. For four years he was the World Record holder and “King” of the 200 meter backstroke.

It started just after the Rome Olympics and finished just before Tokyo in 1964. In between, he victoriously represented the USA in Japan, South America, and Europe and was The American Swimmer of the Year in 1962. Stock had only two coaches, Dave Stacy at Bloomington, Illinois and “Doc” Counsilman at Bloomington, Indiana. He missed making the 1960 U.S. Olympic team by a judge’s decision. They took only two and not three as chosen in previous Olympics.

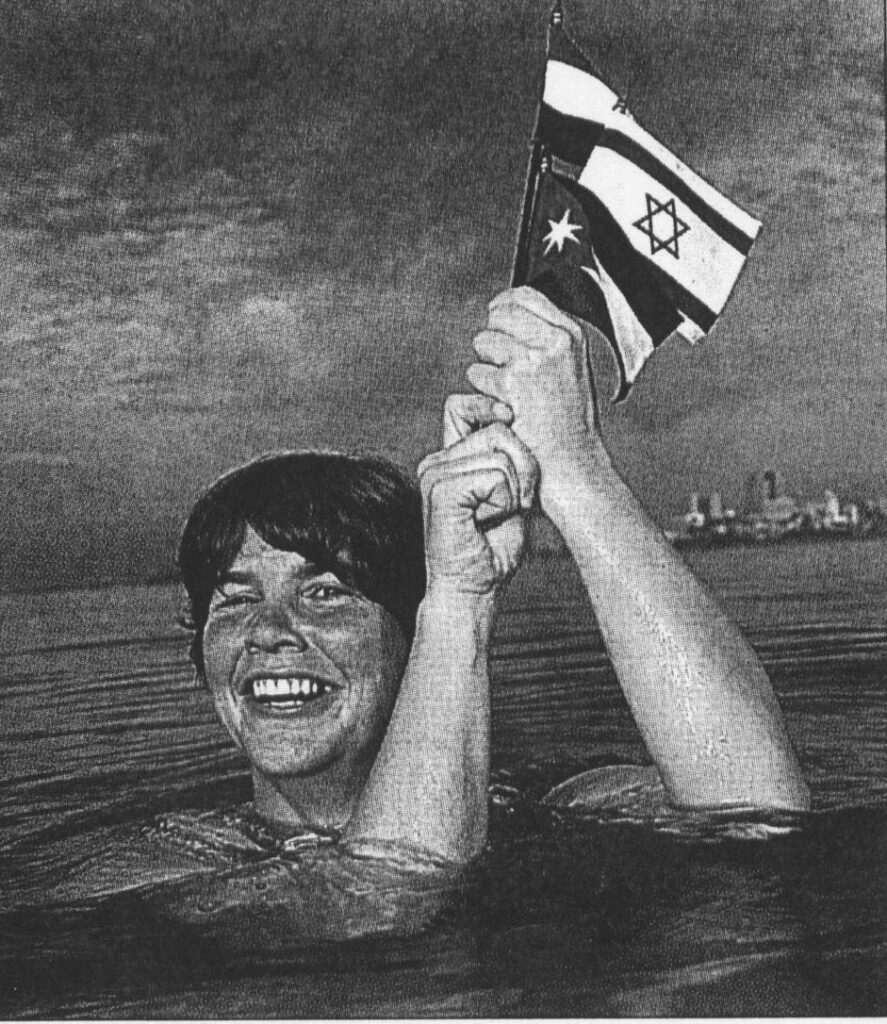

Salute to Women’s History Month: Dawn Fraser and the First Olympic Three-Peat

Dawn Fraser – Photo Courtesy: Dawn Fraser Collection

by John Lohn – Editor-in-Chief

Salute to Woman’s History Month: Dawn Fraser and the First Olympic Three-Peat

On October 11, 1964, the Olympic Games in Tokyo opened. During the week in Japan, Australian star Dawn Fraser made history by capturing the 100-meter freestyle for the third consecutive time. The feat was the first of its kind in Olympic swimming.

Find an expert on the sport and ask that individual to identify the greatest male and female swimmers in history. The answer for the guys is usually instantaneous: Michael Phelps. Truthfully, any other answer reveals foolishness. Obtaining a majority among the gals is much more difficult. Tracy Caulkins and Janet Evans are in the conversation. Arguments are made for Krisztina Egerszegi. Despite her active status, Katie Ledecky has already achieved such greatness that votes are cast on her behalf.

Photo Courtesy: Dawn Fraser Collection.

The other contender for female GOAT status (Greatest of All Time) requires a trip back in time of more than a half-century. It also requires a trip Down Under. Back then, and there, is where Dawn Fraser is found. Hailing from a nation with a rich aquatic history, Fraser spent the middle part of the 1900s establishing herself as a freestyle legend.

There haven’t been many stretches over the past century-plus in which Australia has been a non-player on the international scene. But when Fraser came along in the early 1950s, there was a lull in the Aussie ranks. It was Fraser who lifted her nation back to prominence, first capturing back-to-back gold medals at the 1956 and 1960 Olympics. She then used the Games of 1964 as a stage for history, for it was that Olympiad in which Fraser became the first swimmer to win three consecutive titles in the same event, doing so in the 100 meter freestyle.

Just how challenging is an Olympic trifecta? Consider this fact: The club of three-peaters only features a quartet of members: Fraser, Egerszegi, Phelps and Ledecky.

Setting the Stage

Before celebrating Fraser’s historical achievement from Tokyo, there must first be a look at how she came to pursue the triple. It can be easily argued that her rise to stardom hinged on her crossing paths in 1950 with Harry Gallagher, the man who would coach Fraser to excellence. While talent is obviously the key ingredient for any global success, it must be nurtured and molded, and Gallagher had the perfect approach for working with Fraser.

Fraser wasn’t the easiest of pupils with whom to work. She could be hard-headed and rebellious. She was brash. She could be defiant. Yet, Gallagher knew how to work with these traits, and devised a blueprint that took Fraser’s unquestioned skill set to the greatest heights.

“Dawn was a horror,” Gallagher once said. “She told me I was a deadbeat, to drop dead, to piss off, to get lost. She wasn’t going to do what I wanted her to do. No guy would ever get her to do what she didn’t want to do. She had wild aggression. She reminded me of a wild mare in the hills that you had put the lightest lead on to keep her under control. She wanted to do her own thing. If you had to guide her, it had to be very subtly, so she didn’t understand that she was being manipulated. I used to say that, you know, ‘Dawn, no girl has ever done this before, and I don’t think you can do it either, but you just might be able to do it.’ She’d say, ‘What do you bloody mean? Of course I can bloody well do it.”

Gallagher’s psychological genius and Fraser’s talent proved to be a perfect combination. While Gallagher recognized how to work with his star athlete, Fraser understood the importance of Gallagher as a mentor, and a give-and-take relationship was established. At the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne, the partnership yielded the tandem’s finest moment to date. Behind a world-record performance, Fraser defeated compatriot Lorraine Crapp for gold in the 100 freestyle, simultaneously sparking her legendary status.

Following her Olympic breakthrough, Fraser etched herself as the globe’s premier female swimmer. She set multiple world records in the 100 and 200 free, and entered the 1960 Olympics in Rome as the heavy favorite to repeat in the 100, considered the sport’s blue-ribbon event. Indeed, Fraser prevailed in dominant fashion, as the Aussie bettered American Chris von Saltza by more than a second, an eternity in a two-lap event.

History for the Legend

Had Fraser opted for retirement following the 1960 Games, she would have walked away as an icon. It was rare during that era for swimmers to hang around for multiple Olympiads, let alone three. But Fraser has always been known for bucking the system and prolonging her career, and time on top only added to her legacy.

Photo Courtesy: Delly Carr (Swim Australia/Ascta)

As the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo beckoned, Fraser continued to flourish. Additional world records fell, and in 1962, she became the first woman to crack the one-minute barrier in the 100 freestyle. For all she had previously achieved, Fraser was getting better and was seemingly headed to her third Olympiad as an undeniable force. Of course, not all plans unfold smoothly.

Seven months before the Tokyo Games, Fraser endured a physically and emotionally crippling life event. Leaving a fund-raiser, Fraser was the driver of a car that also carried her mother, sister and a friend. During the ride home in the early-morning hours of March 9, 1964, Fraser was forced to veer out of the way when her car suddenly came upon a truck. When Fraser swerved, her car flipped over, leading to disastrous results. While Fraser, her sister and friend were injured, Fraser’s mother was killed, pronounced dead upon arrival at the hospital. Fraser’s brother initially informed her that their mother died of a heart attack prior to the crash, but as Fraser prepared to write her autobiography, she learned that her mother’s death was actually the result of injuries suffered in the car accident.

“I was led to believe by my family for many, many years, that my mother had died prior to the accident,” Fraser wrote in her autobiography. “I did not feel good inside, but I know I’ve wiped away that question mark in my mind. Over the years, I’ve realized you can beat yourself up at night, lose sleep…but you can’t change the past. My parents taught me to accept things the way they were, the rights and the wrongs…and to learn from my mistakes.”

With the car accident so close to the Olympics in Tokyo, questions rightfully arose concerning Fraser’s ability to three-peat. Really, Fraser would have been excused had she bypassed a third Olympics. Not only was she carrying the enormous weight of her mother’s death, but the crash also left Fraser with a chipped vertebra that forced her to wear a neck brace for nine weeks. More, doctors advised her not to dive off starting blocks due to the risk of furthering her neck injury. It wasn’t until the Olympics in which Fraser dove off the blocks with full force.

As Fraser prepared to chase a third straight gold medal in the 100 free, she wasn’t simply battling her own physical and mental demons. American Sharon Stouder had emerged as a prime challenger, and Fraser would have to produce one of the best efforts of her career to retain her crown. Ultimately, that is what the Aussie managed, as she came through in the final to clock an Olympic record of 59.5, ahead of the 59.9 produced by Stouder.

In less than a minute of race time—but with years of work and dedication providing fuel—Fraser had become the first swimmer to win the same event at three consecutive Olympiads. It was truly a remarkable feat, a triumph well ahead of its time. Years down the line, Egerszegi joined Fraser in the special club, winning the 200 backstroke at the 1988, 1992 and 1996 Games. Eventually, Phelps was given his key, too, and went a step further by winning the 200 individual medley at four consecutive Games (2004-16). Last summer, Ledecky pulled off the feat. But Fraser will forever be the president emeritus of the Three-Peat Club.

It is worth noting that America’s first sprint star, Duke Kahanamoku, could have beaten Fraser to the treble. Kahanamoku was the Olympic champion in the 100 free in 1912 and 1920, but had his 1916 Olympic opportunity stolen by the cancellation of the Games due to World War I.

“I put myself under a lot of pressure by deciding to go to Tokyo, and I also put myself under a lot of pressure to compete in the same event in three Olympics,” Fraser said. “I had, at the back of my mind, that this was for my mother because we were saving up for my mother to go to Tokyo with me. I just imagined that she was there and that I was doing it for her.”

An Extra Souvenir

If Fraser’s excellence in the pool cemented her identity as an all-time great, her third gold medal in the 100 free apparently wasn’t enough of a souvenir from her visit to Tokyo. After completing her work in the pool, the rebellious Fraser set out on a night excursion with Howard Toyne, an Australian Olympic team doctor, and Des Piper, a member of Australia’s field hockey team. The trio planned on obtaining some Olympic flags that lined the street leading to the Imperial Palace, the main residence of the Emperor of Japan.

Dawn Fraser’s three-peat in the 100 freestyle remains an iconic achievement in the sport.

After getting two flags in their possession, police were alerted, and Fraser and her countrymen were arrested, taken to the police station and threatened with jail time. However, Fraser’s prominence was soon revealed, and all three Aussies were released, the lieutenant of the police station actually allowing Fraser to keep one of the stolen flags.

“After showing them my gold medal and my dog tags, (the police) were still very disgusted that I’d…that it was me…that I would do that,” Fraser said. “They explained to me that it was a stealing offense, and it could mean a jail term. But they decided then because of who I was, Dawn Fraser, they let us off.”

The Tokyo police may have been lenient with Fraser, but Australian Swimming was tired of its Glory Girl and her antics. The organization saw the flag incident as a third strike against Fraser. Prior to the flag shenanigans, Fraser—against team orders—walked in the Opening Ceremony in Tokyo, rather than rest. She also donned a suit for competition that she felt was more comfortable, but was not the team-sponsored suit. The accumulated offenses led Australian Swimming to institute a 10-year ban against Fraser, a decision that led to her retirement.

Although the ban was lifted prior to the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City, Fraser didn’t feel like she had the appropriate amount of time to come out of retirement and prepare for a pursuit of a fourth consecutive title in the 100 free. It was the end.

Ahead of Her Time

When the Olympic Games return to Tokyo next summer, only Ledecky has the chance to become the fourth member of the illustrious Three-Peat Club. Ledecky has the opportunity to triple in the 800 freestyle, and the fact that she is the lone individual who can three-peat—particularly in this era of lengthened careers—speaks to the difficulty of the challenge.

Considering Fraser achieved the feat at a time when careers were primarily one-Olympics-and-done only emphasizes that she was ahead of her time and set a spectacularly high bar to chase. Although it will never be known, one also must wonder if Fraser—a multi-time world record holder in the event—could have also managed the accomplishment in the 200 freestyle, which did not become an Olympic event for women until 1968.

Memorable moments are sure to develop at the 2020(2021) Games, and as these new memories are celebrated, what Dawn Fraser achieved in Tokyo 57 years earlier is sure to be celebrated, too. History never disappears. Instead, it serves as a reminder of the past and the greatness that came before and should never be forgotten. For Fraser, she will always be the first swimmer to win Olympic gold in the same event at three consecutive Games, each victory defined in its own way, but the last defining history.

“I can remember precisely what I said,” Fraser stated about the completion of her triple. “I said to myself, ‘Thank God that’s over!’”

April Featured Honoree: Johnny Weissmuller (USA) and his Memorabilia

Each month ISHOF will feature an Honoree and some of their aquatic memorabilia, that they have so graciously either given or loaned to us. Since we are closed, and everything is in storage, we wanted to still be able to highlight some of the amazing artifacts that ISHOF has and to be able to share these items with you.

We continue in the new year, April 2025, with 1965 ISHOF Honoree Johnny Weissmuller, Honor Swimmer. Johnny Weissmuller donated many fabulous things to ISHOF and we want to share some of them with you now. Also below is his ISHOF Honoree bio that was written the year he was inducted.

As a Salute to Women’s History Month, we celebrate Open Water Swimming Pioneer Lynne Cox

LYNNE COX (USA) 2000 Honor Open Water Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: First crossing of the Catalina Island Channel (1971) 12:36 hrs.; Women’s and men’s record crossing of the English Channel (1972) 9:57 hrs.; Women’s and men’s record crossing of the English Channel (1973) 9:36 hrs., Catalina Island Channel crossing record (1974) 8:48 hrs.; Cook Straits between North and South Islands of New Zealand (1975) 12 hrs., 2 min.; Straits of Magellan (Chile), Oresund and Skagerrak (Scandinavia) (1976) 1 hr., 2 min.; Aleutian Islands (three channels) 1977; Cape of Good Hope (S. Africa) 1979; Around Joga Shima (Japan) 1980; Across three lakes in New Zealand’s Southern Alps (1983); Twelve difficult “Swims Across America” (1984); “Around the World in 80 Days”, 12 extremely challenging swims totaling 80+ miles (1985); Across the Bering Strait, U.S. to Soviet Union (1987) 2 hr., 6 min.; Across Lake Baikal, Soviet Union (1988); Across the Beagle Channel between Chile and Argentina (1990); Across the Spree River between the newly united German Republics (1990); Lake Titicaca Swim (1992).

Lynne Cox became the best cold water, long distance swimmer the world has ever seen. Her 5 foot 6 inch, 180-pound frame of a body was at one with the water. With a body density precisely that of sea water, her 36% body fat (normal is 18% to 25%) gave her neutral buoyancy. Her energy could be used all for propulsion and not to keep afloat. Propelling though the most treacherous waters of the globe is what Lynne Cox did best.

When her parents moved the family from New Hampshire to Los Alamitos, California in 1969 so that Lynne and her older brother and two sisters could receive better swim coaching, Hall of Fame coach Don Gambril, at the Phillips 66 Swim Club, took her under his guidance. What he saw was a large-boned girl with boundless energy and great upper body strength who could slice through the water like a porpoise. When she was 14 and already tired of “going back and forth in the pool and going nowhere”, Gambril urged her to enter a series of rough water swims near Long Beach. As a result in 1971, at age 14, she swam the 31-mile Catalina Channel in Southern California with four other friends. She loved it. The chill, the chop, the solitude, and the liberation were all exhilarating to Lynne. “Everything opened up. It was like going from a cage to freedom.”

For the next two decades, Lynne competed against the elements in swims which took her to all the major bodies of water in the world, many of which had not been crossed before and most of which had not been done by a woman. Her study of history at the University of California Santa Barbara may have been a catalyst in choosing which swims to pursue. It became her desire to use her swims to help bring people together, to work toward a more peaceful world. This realization was sparked during her 1975 swim as the first woman to swim the 10-mile Cook Straits in New Zealand in 12 hours 2-1/2 minutes. During this difficult swim, the outcry of support from the New Zealand people was all she needed to finish this 50 degree Fahrenheit swim, even when the tides and current had taken her farther away from the starting point after the first five hours of the crossing.

Her most famous swim was in 1987, eleven years after her father had planted the seed in her head. Lynne completed 2.7 miles in the Bering Straits, 350 miles north of Anchorage, Alaska where the water temperature ranges from 38-42 degrees Fahrenheit. Perhaps the most incredible of cold water swims, her 2 hours, 16 minutes from Little Diomede (USA) to Big Diomede (USSR) astonished the physiologists who were monitoring her swim. It marked one of the coldest swims ever completed. One can’t get much colder. After this temperature, the water turns to ice. It was a swim that brought the United States and Soviet Union together in an exchange of glasnost and perestroika. In Washington, Presidents Reagan and Gorbachov toasted Lynne’s swim saying that she “proved by her courage how closely to each other our peoples live”. Before this time, at the start of the Cold War, the families of the Diomede Islands had been split and had not been permitted to see one another since 1948.

Lynne is the purist of marathon swimmers. She does not wear a wet suit in frigid water and does not use a cage in shark infested waters. Her swims in Iceland’s 40 degree F Lake Myzvtan and Alaska’s 38 degree F Glacier Bay, where the lead boat had to break a path in the one quarter inch ice, were done wearing only a swim suit, cap and goggles. She wanted to do more than just achieve times and set records. And she did. But in the process, she became the fastest person to swim the English Channel (1972 and again in 1973), the first person to swim the Straits of Magellan (Chile) 4-1/2 miles, 42 degree F (1976), Norway to Sweden, 15 miles 44 degree F (1976), three bodies of water in the Aleutian Islands (USA) 8 miles total, 44 degree F (1977) and around the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) 10 miles, 70 degree F which attracted sharks, jellyfish and sea snakes (1978). Many other swims included Lake Biakal in the Soviet Union (1988), the Beagle Channel of Argentina and Chile (1990) and around the Japanese Island of Joga Shima. In 1994 at the age of 37 years, she swam the Gulf of Aqaba in the Red Sea joining the 15 miles of 80-degree water between Egypt, Israel and Jordan. She has swum Lake Titicaca in the Andes Mountains, the world’s highest navigable lake.

Lynne works as an author, motivational lecturer, and teaches swimming technique both in the pool and open water.

Happy Birthday Rebecca Soni!!

Rebecca Soni (USA)

Honor Swimmer (2021)

FOR THE RECORD: 2008 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (200m breaststroke), silver (100m breaststroke, 4×100m medley relay); 2012 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (200m breaststroke, 4×100m medley relay), silver (100m breaststroke); EIGHT WORLD RECORDS: 100m breaststroke (1 LC, 1 SC), 200m breaststroke (3 LC, 1 SC), 4×100 medley relay (1 LC, 1 SC); 2009 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS (LC): gold (100m breaststroke), silver (50m breaststroke); 2011 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS (LC): gold (100m breaststroke, 200m breaststroke, 4×100m medley), bronze (50m breaststroke); 2010 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS (SC): gold (50m breaststroke, 100m breaststroke, 200m breaststroke), silver (4×100m medley relay)

Rebecca Soni is known as a breaststroke phenom. What she lacked in size, she made up for in strength and desire. Her much-discussed technique is what separated her from her rivals. It featured an abbreviated leg kick aligned with perfectly timed rapid arm sweeps. It was an effective and efficient approach, and it was gold – Olympic gold.

Soni is a two-time Olympian and six-time Olympic medalist. She broke eight world records in breaststroke events and as part of two women’s medley relay teams, one long course and one short course.

During the summer of 2006, Soni had a procedure called a cardiac ablation that helped regulate her heartbeat. She had an irregularly high heartbeat that affected her training and needed to be treated.

Soni worked through her health issues and qualified for her first Olympic team in 2008 by winning the 200m breaststroke. In the 100m breaststroke, she took fourth place. However, fate stepped in when one American teammate withdrew and another missed a deadline for the Games, allowing Soni to represent the United States in her first Olympic Games in three events – both breaststrokes and the 4×100 medley relay. She did not disappoint.

In her first event, the 100m breaststroke, Soni won the silver medal behind world record holder Leisel Jones of Australia. She followed with a stunning victory in the 200m breast, out-swimming Jones with a time of 2:20.22 that also broke Jones’ world record.

Soni wrapped up her first Games as a member of the USA medley relay team, taking her second silver medal, behind the Australians.

Soni attended the University of Southern California from 2005-2009 and swam for multi-time Olympic coach Dave Salo. Her career was defined by four national titles in the 200-yd breaststroke and in her junior and senior years, she also won titles in the 100-yd breaststroke. Soni ended her career at USC with the NCAA record in the 200-yd breaststroke, gathered 12 All-American honors and finished as one of the most dominant breaststrokers in NCAA history.

At her second Olympic Games in 2012, Soni again won the silver medal in the 100m breaststroke, this time behind Lithuania’s Ruta Mejlutyte by only .08 seconds. In the 200m breaststroke, Soni broke the world record in the semi-finals with a time of 2:20.00. In the finals, she won the gold medal and broke the world record again with a time of 2:19.59. The effort made Soni the first woman to break 2:20 in the event.

With that gold medal, Soni became the first female to successfully win back-to-back Olympic titles in the 200m breaststroke. In the medley relay, Soni helped the United States win gold, as she teamed with Missy Franklin, Dana Vollmer and Allison Schmitt. Together, the foursome broke the world record with a time of 3:52.05.

After her retirement in 2014, Soni went into business with friend and former Olympic teammate, Caroline Burckle. They co-founded a company called RISE Athletes, an online mentoring platform for young athletes. Soni’s company recruits Olympians to help mentor young athletes by using one-on-one interaction.

Happy Birthday Tom Gompf!!

Tom Gompf (USA)

Honor Contributor (2002)

FOR THE RECORD: 1964 Olympic Games: bronze (10m platform); 3 National AAU Championships: (trampoline-1, 10m platform-2); 4 Foreign National Championships: Japan (3), Spain (1); 2 World Professional High Dive Championships; 11 years Diving Coach: University of Miami (FL) (1971-82); 1976, 1984 U.S. Olympic Diving Team: Coach/Manager; U.S. Olympic Committee Executive Board of Directors: Member (1977-2000); 1984-2004 FINA Technical Diving Committee: Chairman (1988-2000); U.S. Diving, Inc.: President (1985-90); U.S. Aquatic Sports: President (1999-present); Executive Board of Amateur Swimming Union of the Americas: member (1999-present).

Tom Gompf loves all aspects of diving; always has, always will. He started as a young local

competitor, advanced to the Olympic Games, performed in professional competition and grew to serve the international diving community as an administrative leader. He is a hard worker for the good of the sport and a friend to all. Gompf has had a profound international influence on the sport of diving.

As a youngster, growing up in Dayton, Ohio, Tom won five National YMCA Diving titles and two National AAU Junior Nationals Championships. He was coached in the early years by Ray Zahn, George Burger and Lou Cox.

By the time he graduated from college at Ohio State University in 1961, diving for Hall of Fame Coach Mike Peppe, Tom had won the NCAA National Trampoline Championships and a year later, the U.S. National AAU Diving Championships twice on the 10m platform. In 1964 at the Tokyo Olympics, and under the eye (1961-1965) of coach Dick Smith, Tom won the bronze

medal on the 10m platform, only two points behind gold medalist Bob Webster (USA) and one point behind silver medalist Klaus Dibiasi (Italy) both Hall of Famers. Tom went on to win National Championships in Spain and Japan and then competed in and won first place in the 1970 and 1971 World Professional High Diving Championships in Montreal. His next competition

was diving off the cliffs of Acapulco. He survived. All this was while flying several hundred combat missions in Vietnam from 1965 to 1967 earning the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Force Commendation Medal and the Air Medal with multiple silver clusters.

From 1971 to 1982, he coached diving at the University of Miami (FL) developing divers, winning six National Championships and competing on World, Pan American and Olympic teams. Steve McFarland, Melissa Briley, Julie Capps, Greg Garlich and Greg Louganis were among his team members.

But perhaps Tom’s greatest contribution came from behind the scenes as a leader in the sport. Universally acknowledged for his low-key, amiable manner, his stock-in-trade is his ability to work effectively and silently to promote the sport. Extremely intelligent, he can be very persuasive. Says one veteran, “Tom can make you believe a watermelon is an apple.” Since 1977, he has served on the United States Olympic Committee Board of Directors (1977-2004) and Executive Board, working to autonomize the four aquatic disciplines under the Amateur Sports Act of 1978. He helped establish U.S. Diving, Inc. in 1980 and serves as the only continuous board member. He served four years as its president (1985-90) and since 1998 has been president to United States Aquatic Sports which represents all the disciplines and reports directly to FINA.

On the international scene, Tom serves on the Executive Board of the Amateur Swimming Union of the Americas (ASUA). In 1984, he was elected to the FINA Technical Diving Committee and continues in that position today. He served three, four-year terms as chairman during which time he proposed and passed legislation to include 1 meter diving in the FINA World Championships (1986) and synchronized diving for World competitions, with its debut at the 2000 Sydney Olympics. “It lends the element of team, which every other sport has. It’s TV and a proven crowd favorite,” says Tom. Tom is responsible for the renovation of international judging, initiating a judges’ education program involving clinics and manuals. Tom has served as the

Chairman of the FINA Diving Commission for the World Swimming Championships (1990-98) and as Chairman of the FINA Diving Commission for the Olympic Games (1992-2000).

Tom has received the FINA silver and gold pins, served as the U.S. Team Manager for the 1976 and 1984 Olympic Games, was Chairman eight years (1991-98) for the ISHOF Honoree Selection Committee and served four years (1986-90) on the ISHOF Board of Directors. All the while, Tom was airline captain for National (1967-80), Pan American (1980-91) and Delta Airlines (1991-2000). He has received the Mike Malone/Glen McCormick Award (1984) for outstanding contribution to U.S. Diving, the Phil Boggs Award (1995), U.S. Diving’s highest award and the 1997 Paragon Award for competitive diving.

Tom’s accomplishments were never for personal fame, but always an honest attempt to help the sport he loves. He has applied the same determination and passion that made him an Olympic medalist to pursuing the goal of advancing and improving all aspects of diving on the international scene for the good of the sport and the athletes.

Today We Remember Honoree and Long Time ISHOF Friend Ron O’Brien on His Birthday!!

Ron O’Brien (USA)

Honor Diver (1988)

FOR THE RECORD: NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS: 1959 (one meter); AAU NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: 1961 (3 meter); OLYMPIC COACH: 1972, 1976, 1980, 1984, 1988; Assistant Coach: 1968; WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS COACH: 1975, 1978, 1982, 1986; PAN AMERICAN COACH: 1967, 1975, 1983, 1987; WORLD CUP COACH: 1981, 1983, 1985, 1987; 1974 Malone Memorial Award; 1976 Fred Cady Award; 1979-1987 Mike Peppe Award; 1984 Ohio State University Sports Hall of Fame; Winner of 62 National Team Championships while coaching at University of Minnesota (1962-1963); Ohio State (1963-1978), Mission Viejo (1978-1985) and Mission Bay (beginning 1985-1988).

Ron O’Brien has done it all in diving from NCAA and AAU national champion under Mike Peppe while a six letter man (gymnastics and diving) at Ohio State to the top professional water show act (with Hall of Famer Dick Kimball), to the Ph.D. that made believers out of the academicians, to a top college, club, national and international coach. He has won U.S. Diving’s Award as the “Outstanding Senior U.S. Diving Coach” every year since the award was inaugurated in 1979.

It seems like Ron O’Brien has always been a diving coach. Standing next to the deep end (now a diving well), speaking in sort of a stage whisper, animated by body language and hand signals of what the diver did or did not do. His face is constantly sunburned–his green eyes bloodshot with crinkle smile lines around his mouth. His ears and nose peeling as he does a dance in place, teetering on the edge of the pool.

In his first 25 years of coaching, his divers have won 154 gold, 90 silver and 78 bronze medals in major Olympic, world, national, NCAA and Big Ten Conference diving championships. This doesn’t take into account the dozens of medals in prestigious invitational meets around the world. He has coached everyone from beginners to the famed Greg Louganis.

Ron narrowly missed the 1960 Olympic team himself placing third or fourth in the Olympic trials where only two were taken. Perhaps this experience gave him the patience, persistence and understanding to be the coach of every Olympic team since 1968. “It certainly was a good motivator,” he says. “It made me want to make it as a coach. But what keeps me going is not winning,” O’Brien says, “but the quest for reaching potential in myself as a coach and my kids as divers. It’s the pursuit of excellence.”

If you had to pick a highlight from his first 25 years of coaching at Minnesota, Ohio State and the two Missions, it might be the 1982 World Championships when O’Brien’s divers from Mission Viejo won all four of the diving gold medals, the first and only time this has happened in diving history.

In honor of Women’s History Month, Hilda James: One of the great early female pioneers and feminists!

Hilda James (GBR) 2016 Honor Pioneer Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: 1920 OLYMPIC GAMES: silver (4x100m freestyle); SEVEN WORLD RECORDS: two (300yd freestyle), two (150yd freestyle), one (440yd freestyle), one (400m freestyle), two (220yd freestyle), three (300m freestyle); 29 ENGLISH RECORDS: four (300yd freestyle), one (440yd freestyle), one (500yd freestyle), four (220yd freestyle), four (100yd freestyle), four (150yd freestyle), two (440yd freestyle), two (500yd freestyle), one (440m freestyle), one (1750yd freestyle), one (880yd freestyle), one (1000yd freestyle); EIGHT U.K. NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: four (220yd freestyle), one (100yd freestyle), two (Thames Long Distance from Kew Putney five miles 50yd), one (440yd freestyle); FOUR SCOTTISH RECORDS: one (220yd freestyle), two (200yd freestyle), one (300yd freestyle), one (400m freestyle); FOUR OTHER MEET RESULTS: gold (300yd individual medley), gold (220yd freestyle), gold (110yd breaststroke), one River Seine 8k Race.

To avoid attending Church of England religious education classes, which conflicted with her parents religious beliefs, this 11-year old Liverpudlian was assigned to swimming classes at the Garston Baths.

Five years later, Hilda James was Great Britain’s best female swimmer and left for the 1920 Olympic Games with high expectations. Unfortunately in Amsterdam, the USA women completely dominated, sweeping the gold, silver and bronze medals in the 100m and 300m freestyle, the only individual swimming events for women at the 1920 Games. And while the British did win silver medals in the 4x100m relay, they finished a full 30 seconds behind the Americans. The following day Hilda cheekily asked the American coach, Lou de B. Handley, to teach her the American Crawl.

In 1922, Hilda was invited by her American friends to visit the USA for the summer racing season. While she was still behind the American stars Helen Wainwright and Gertrude Ederle, she was closing the gap.

By 1924, Hilda held every British and European freestyle record from 100 meters to the mile, and a handful of world records as well. She easily made the 1924 Olympic team, and it was widely believed that she would return from Paris with a handful of medals. When Hilda’s mother insisted she accompany her daughter as chaperone, and the British Olympic Committee refused, Hilda’s mother refused to let her go. Unfortunately, Hilda was not yet 21, was under the care of her parents – and had to obey.

Hilda turned 21 shortly after the Olympic Games, gained her independence, and took a job with the Cunard Shipping Company, traveling the world as a celebrity spokesperson, at a time when women were just starting to gain their freedom.

We will never know how Hilda would have fared in the 1924 Olympic Games, but she was a trailblazer and one of Europe’s first female sports superstars who inspired future generations of girls to follow in her wake.

From Hilda’s grandson: Ian Hugh McAllister:

Ian Hugh McAllister

Tynemouth Outdoor Pool

tFenSbcpodroungssagaeryr lo5tnarm, e2d0d1a4 · Poole, United Kingdom ·

My Grandmother Hilda James officially opened the pool in 1925. As the premiere swimming star of the era she was also invited to participate in the opening gala but declined to swim in the races, substituting a demonstration of trick and fancy swimming instead. What the audience didn’t know was that she had already signed as a professional with Cunard, and was due to become the first celebrity crew member aboard Carinthia, the very first purpose-built cruise liner. Although not officially on the Cunard payroll until the following week, she was not exactly sure when they would start paying her, and dared not compete in case the press found out she was no longer an amateur. It was a poignant moment for Hilda, her last ever appearance as an amateur following a meteoric nine year career. During that time she held an Olympic silver medal, broke seven World Records, and actually introduced the crawl stroke to the UK.

The whole story is told in her biography “Lost Olympics” which was published last year on Amazon and for Kindle download. Please visit the Lost Olympics facebook page for a lot more information, including my various TV and radio interviews etc. Hilda has recently been nominated for induction to The International Swimming Hall of Fame.

When the pool gets rebuilt, can I come and open it again for you, or at least be at the opening? (although I am no swimmer!)

If you are interested in purchasing a copy of The Hilda James story: Lost Olympics, please reach out to meg@ishof.org