Chinese Diver Guo Jingjing to be inducted with Class of 2025

Guo Jingjing, Honor Diver, China, who was inducted as part of the Class of 2016, but was unable to be officially inducted with her Class, will join us in Singapore to be officially inducted with the Class of 2025. Jingjing will travel to Singapore to attend the World Championships and be officially inducted into ISHOF on July 28, 2025. Here is her Honoree Biography from 2016:

Guo Jingjing (CHN)

Honoree Type: Diver

FOR THE RECORD: 2000 OLYMPIC GAMES: silver (3m synchro, 3m individual); 2004 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (3m synchro, 3m individual); 2008 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (3m synchro, 3m individual); 1998 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: silver (3m individual); 2001 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (3m individual, 3m synchro); 2003 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (3m individual, 3m synchro); 2005 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (3m individual, 3m synchro); 2007 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (3m individual, 3m synchro); 2009 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (3m individual, 3m synchro); 1998 ASIAN GAMES: gold (3m individual); 2002 ASIAN GAMES: gold (3m individual, 3m synchro); 2006 ASIAN GAMES: gold (3m synchro); 2001 SUMMER UNIVERSIADE: gold (1m individual, 3m individual, platform synchro); 2003 SUMMER UNIVERSIADE: gold (3m synchro), silver (1m individual, 3m individual); 2005 SUMMER UNIVERSIADE: gold (1m individual, 3m synchro).

She enjoyed a very normal childhood growing up in the city of Baoding in the province of Hebei, until 1988, when a diving scout visited her school. The scout asked the students if anyone wanted to learn how to dive and Guo Jingjing eagerly volunteered, believing she was signing up for swimming.

After realizing her mistake, she found she liked the challenge and grew to enjoy the training. Eventually she developed the goal of competing and winning a gold medal. She proved not only to be incredibly gifted, but fearless and focused.

Eight years later, at the age of 14, Guo made her Olympic debut at the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, finishing fifth on the 10-meter platform event. After those Games, her coach Yu Fenwhen, retired and Jingjing came under the tutelage of Zhou Jihong, China’s first Olympic diving gold medalist.

Under Zhou, she moved from the tower to the spring board at the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney, Australia and won silver medals in both the 3-meter springboard and 3-meter synchronized diving events with partner, Fu Mingxia.

After the 2000 Games, her partner Fu Mingxia retired. Guo then paired up with Wu Mingxia and did not miss a beat. Enduring grueling training sessions, sometimes lasting six to eight hours a day, she won double gold medals at five FINA World Championships and two Olympic Games between 2001and 2009.

In front of a hometown crowd in Beijing, in the Summer of 2008, Guo Jingjing became the most decorated female Olympic diver and tied fellow Chinese athlete, Fu Mingxia and Americans Pat McCormick and Greg Louganis with the most individual Olympic diving gold medals (four). In the synchronized event, defending champions Jingjing and Wu Mingxia led the entire competition, capturing the gold medal in their homeland.

With nothing else to prove, she, like fellow 2016 honoree Aaron Peirsol, announced her retirement in 2011, leaving the London Olympic Games to younger talents on her team.

Instead of London, Guo Jingjing was married in 2012 and now has one son, Lawrence. The family lives peacefully in Hong Kong, where Jingjing continues her career as a model and celebrity spokeswoman.

The information on this page was written the year of their induction

ISHOF announces Masters Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony and ISHOF Awards Evening: September 13, 2025 at the Sonesta Fort Lauderdale

ISHOF is proud to announce that it will be hosting this year’s Masters International Swimming Hall of Fame (MISHOF) Honoree Induction Ceremony along with the ISHOF Specialty Awards Saturday, September 13, 2025 at the Sonesta Fort Lauderdale Beach, located at 999 Fort Lauderdale Beach Blvd.

In addition to the MISHOF Induction and the ISHOF Specialty Awards, ISHOF will once again be the site of the ISHOF (Coaches) Clinic, who recently partnered with the American Swimming Coaches Association (ASCA). Last month ASCA announced it was officially taking over the management and operation of the longstanding and popular clinics, including the Central States and Eastern States Swim Clinics, as well as the ISHOF Clinic effective in 2025. These clinics, renowned for their high caliber coach speakers and overall contributions to the professional development of swim coaches and athletes for more than four decades, will now be under ASCA’s guidance and leadership, partnering with ISHOF Honoree and Board Member, Coach Mark Schubert.

MISHOF’s Class of Honorees includes swimmers, Diann Ustaal and Charlotte Davis of the USA, Tony Goodwin (AUS) and Hiroshi Matsumoto (JPN); Diver, Rolf Sperling (GER), Artistic Swimmer, Joyce Corner* (CAN), Water Polo Player, Gary Payne (AUS) and Contributor for Artistic Swimming, Barbara McNamee (USA). “It’s quite a remarkable group”, said Bruce Wigo, ISHOF Historian, and former CEO; “We look forward to welcoming them all to Fort Lauderdale this Fall!”

Nominations are still open for the ISHOF Aquatic Awards and ISHOF Specialty Awards, so send in your nominations to meg@ishof.org

Once we have more detailed information on the program, links to make reservations for the hotel and the exact schedule, we will post more on line and on social media.

deceased

See you this Fall!

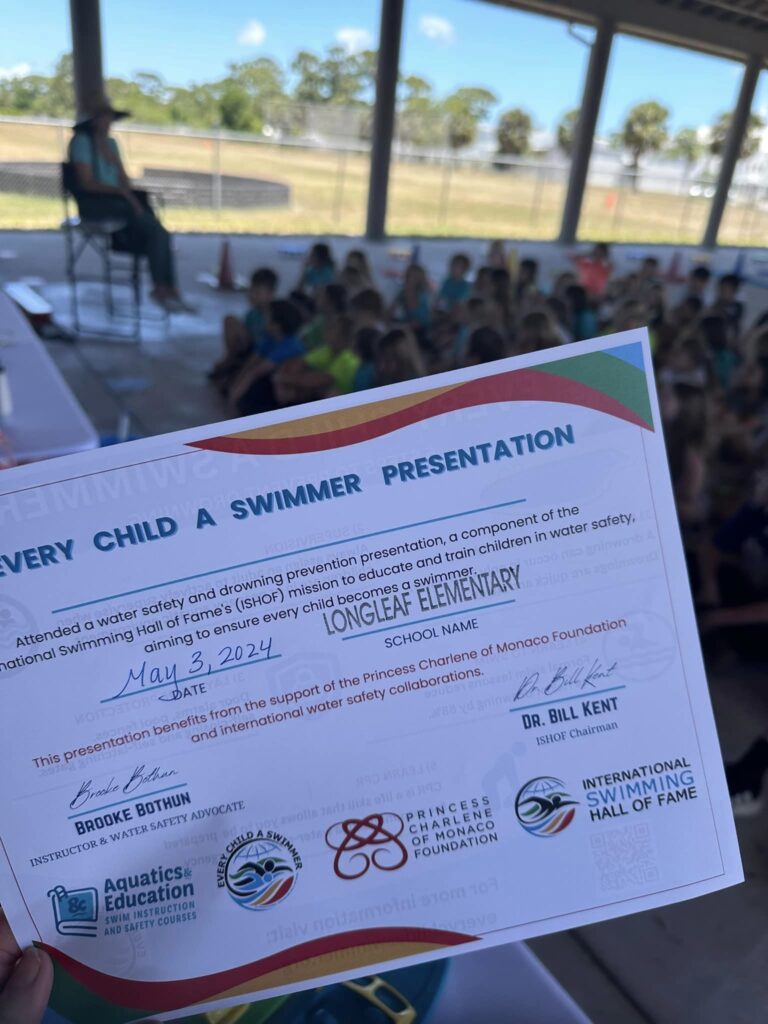

Every Child A Swimmer Update ~ March 2025

Collaborative Success: Advancing Water Safety Education

Every Child A Swimmer (ECAS), Aquatics & Education, LLC., and the Princess Charlene of Monaco Foundation are proud to present this report detailing the incredible success of our collaborative water safety education program. Through this partnership, and in coordination with Brevard Public Schools in the State of Florida, we reached over 10,000 students, providing critical water safety education and emergency preparedness training.

Through whole-group instruction and experiential learning opportunities, students gained essential knowledge on drowning prevention, water safety best practices, and emergency response strategies. The overwhelmingly positive response from students, teachers, and school administrators underscores the need for continued and expanded programming in the future.

Year-Round Commitment to Safety and Learning This collaborative effort is dedicated to promoting safety and learning year-round in the State of Florida. Each grade-level presentation is carefully designed to be age-appropriate and engaging, ensuring students receive valuable and relevant water safety education tailored to their developmental stage.

Interagency Collaboration & Community Impact Collaboration has been central to the program’s success. ECAS, Aquatics & Education, LLC., and the Princess Charlene of Monaco Foundation worked closely with local fire departments to deliver these presentations, enriching the curriculum with their expertise. This partnership provided students with a broader understanding of first responders’ critical roles, highlighting that firefighters serve not only as fire responders but also as primary emergency medical professionals.

The program’s focus on water safety education, drowning prevention awareness, and emergency response training is essential for equipping youth with life-saving skills. By fostering interagency cooperation and community engagement, we aim to continue expanding the reach and impact of this vital initiative.

Program Implementation & Future Goals The implementation of this water safety education program marks a groundbreaking step toward drowning prevention in the State of Florida. Moving forward, ECAS, Aquatics & Education, LLC., and the Princess Charlene of Monaco Foundation remain committed to expanding this initiative, enhancing curriculum offerings, and securing additional partnerships to ensure every child has access to essential water safety education.

Stay connected with the Every Child a Swimmer program as we continue to build a safer future for our youth through collaboration and innovation!

Follow us on social media @everychildaswimmer

ISHOF salutes Black History Month: Remembering the Tennessee State Tigersharks

Left to Right, First Row: Captain Meldon Woods, Co-Captain Clyde Jame, Ronnie Webb, Jesse Dansby, Osborne Roy, Cornelias Shelby, Frank Oliver, James Bass and Roland Chatman. Second Row: Cecil Glenn, William Vaughn, Raymond Pierson, Robert Jenkins, George Haslarig, Leroy Brown, Frank Karsey, John Maxwell and Coach Thomas H. Hughes.

The Tennessee State University Tigersharks finished the 1960 – 61 swimming season with a 6 – 1 record, losing only to Indiana’s Ball State University, one of two white schools willing to swim TSU. The first time they met in the 1950s, TSU won. Co-captain Clyde James, was a finalist in the NAIA National Championships in the 100 yard butterfly. Clyde went on to become a legendary coach at the Brewster Recreation Center and Martin Luther King HS in Detroit. Tennessee State started its swimming team in 1945 and it’s coach, Thomas “Friend” Hughes was the first African American accepted as a member of the College Swimming Coaches Association in 1947.

Black History Month: Despite Stolen Gold, Enith Brigitha Was a Sporting Pioneer

By John Lohn, Editor, Swimming World

Emerging as a youth star from the island nation of Curacao in the Netherlands Antilles, Brigitha etched herself as one of the world’s most consistent performers during the 1970s, appearing in a pair of Olympic Games and three versions of the World Championships. More, she was a regular medalist at the European Championships.

It didn’t take long for Brigitha to become a known entity in the pool, such was her talent in the freestyle and backstroke events. But there was another factor that made the Dutchwoman impossible to miss. On a deck filled with white athletes, Brigitha stood out as one of the few members of her race to step onto a starting block, let alone contend with the world’s best.

In Montreal in 1976, Brigitha captured bronze medals in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle to become the first black swimmer to stand on the podium at the Olympic Games. The efforts delivered a breakthrough for racial diversity in the sport and arrived 12 years ahead of Anthony Nesty’s historic performance. It was at the 1988 Games in Seoul in which Nesty, from Suriname, edged American Matt Biondi by .01 for gold in the 100 butterfly.

Photo courtesy: Enith Brigitha

What Brigitha achieved in Montreal fit neatly with the progression she showed in the preceding years. After advancing to the finals of three events at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich, Brigitha was a medalist in her next five international competitions. It was this consistency that eventually led to Brigitha’s 2015 induction into the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

“(It meant a lot) to be told by a coach, ‘We believe in you. You are going to reach the top,’” Brigitha said during her induction speech into the Hall of Fame. “It is so important that people express trust in you and your qualities when you are working on your career. I am very grateful to all the people who were there for me when I needed them the most.”

Photo Courtesy: Enith Brigitha

Brigitha’s first medals in international competition were claimed at the inaugural World Championships. In Belgrade, Yugoslavia, Brigitha earned a silver medal in the 200 backstroke and added a bronze medal in the 100 freestyle. That performance was followed a year later by a five-medal haul at the European Championships, with four of those medals earned in individual action. Aside from winning a silver medal in the 200 freestyle, Brigitha collected bronze medals in the 100 freestyle and both backstroke events.

Bronze medals were added at the 1975 World Championships in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle and carried Brigitha into her second Olympiad. A silver medal in the 100 freestyle marked her lone individual podium finish at the 1977 European Championships, while the 1978 World Champs did not yield a medal and led the Dutch star into retirement.

Shirley Babashoff Kornelia Ender and Enith Brigitha 1973 – Photo Courtesy – NT/CLArchive

Despite her success, which twice led to Brigitha being named the Netherlands’ Athlete of the Year, her career is also defined by what could have been. No two athletes were more wronged by East Germany’s systematic doping program than Brigitha and the United States’ Shirley Babashoff. At the 1976 Olympics, Babashoff won silver medals behind East Germans in three events, prompting the American to accuse – accurately, it was eventually proved – her East German rivals of steroid use. For her willingness to speak out, Babashoff was vilified in the press, called a sore loser and tagged with the nickname, “Surly Shirley.”

Brigitha experienced similar misfortune while racing against the East German machine. Of the 11 individual medals won by the Dutchwoman in international action, she was beaten by at least one swimmer from the German Democratic Republic in 10 of those events. Her bronze medal in the 100 freestyle is the performance that stands out.

In the final of the 100 free in Montreal, Brigitha placed behind East Germany’s Kornelia Ender and Petra Priemer. Upon the fall of the Berlin Wall and the release of thousands of documents of the East German Secret Police, known as the Stasi, it was revealed that Ender and Priemer were part of a systematic-doping program that spanned the early 1970s into the late 1980s and provided countless East German athletes with enhanced support, primarily in the form of the anabolic steroid, Oral-Turinabol.

Had Ender and Priemer not been steroid-fueled foes or been disqualified for their use of performance-enhancing drugs, Brigitha would have been the first black swimmer to win an Olympic gold medal, and her Hall of Fame induction would have come much earlier. Ender was a particular hurdle for Brigitha, as she won gold medals in six of the events in which Brigitha medaled on the international stage.

“Some gold medals didn’t come my way for reasons that are now well-known, namely the use of drugs by my rivals,” Brigitha said. “That gold has come my way (through induction into) the Hall of Fame. I thank the women who set an example and those who crossed the line with confidence and respect, but without the use of drugs.”

Babashoff has been a vocal proponent of reallocation, citing the need to right a confirmed wrong. If nothing else, she has sought recognition from the IOC and FINA that an illicit program was at work and damaged careers. Those pleas, however, have fallen short of triggering change, the IOC unwilling to edit the record book.

Calls have frequently been made for East German medals – Olympic, World Championships and European Champs – to be stripped and reallocated to the athletes who followed in the official results. However, officials from the International Olympic Committee and FINA, swimming’s global governing body, have refused to meet these demands.

“Every once in a while, we’ve looked at the issue hypothetically,” once stated Canadian Dick Pound, a 1960 Olympic swimmer and former Vice President of the International Olympic Committee. “But it’s just a nightmare when you try to rejigger what you think might have been history. For the IOC to step in and make these God-like decisions as to who should have gotten what…It’s just a bottomless swamp.”

Even without an Olympic gold medal that can be considered her right, Brigitha shines as a pioneer. In a sport in which black athletes were rare participants, Brigitha compiled an exquisite portfolio and proudly carried her race to heights that had never before been realized.

Happy Birthday Rowdy Gaines !!!

Rowdy Gaines (USA) 1995 Honor Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: 1984 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (100m freestyle, 4x100m medley relay, 4x100m freestyle relay); 8 WORLD RECORDS: (1-100m freestyle, 2-200m freestyle, 2-4x100m freestyle relay, 3-4x100m medley relay); 1978 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (4x100m freestyle relay, 4x200m freestyle relay), silver (200m freestyle); 1982 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (4x100m medley relay, 4x100m freestyle relay), silver (100m, 200m freestyle); 1979 PAN AMERICAN GAMES: gold (200m freestyle, 4x100m freestyle relay, 4x200m freestyle relay); 1983 PAN AMERICAN GAMES: gold (100m freestyle, 4x100m freestyle relay, 4x100m medley relay, 4x200m freestyle relay), bronze (200m freestyle); 17 U.S. NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: 9 Outdoor, 8 Indoor; 8 NCAA CHAMPIONSHIPS: 50 yd, 100yd, 200yd freestyle; 400m, 800m freestyle relays.

Rowdy Gaines was named after the rambunctious western her in the television series “Rawhide.” He is described by his merits for being “rapidly successful, competitive, and very, very fast” and feels more at home in the water than on land. He has broken eight world records and continues to swim today.

Rowdy loved the water as a child, but did not begin his notorious swimming career until the late age of 17 with a 16th place finish in the Florida High School Championship. The following year, Rowdy came back to win the State championships and quickly developed into a world class contender when he placed second in the 200m freestyle at the World Championships in 1989. Rowdy was recruited to Auburn University where he stroked to American records in the 100 and 200 yard freestyles and to the world record in the 200m freestyle in 1:49.16. By 1980, he was named “World Swimmer of the Year.”

It was at the pinnacle of his swimming career that he suffered a tremendous disappointment when the 1980 US Olympic Team boycotted the Olympic Games. Shortly thereafter, he retired, only to return with a vengeance a year and a half later, determined to regain his place in the swimming world and claim the medals he was unable to obtain in 1980.

Rowdy had no problem grasping three Olympic gold medals amidst roaring fans who believed in the “old man” of the 1984 Olympics. Rowdy’s crowning moments of capturing gold by winning the 100m freestyle and the 4×100 medley and freestyle relays will remain sacred to him and his fans.

Throughout his memorable career, Rowdy won three Olympic gold medals, set eight world records, won seven World Championship medals, not to mention numerous medals in the Pan American Games, US National Championships, and NCAA Championships.

Since his retirement, Rowdy has been asked to endorse many products, has been a swimming commentator for CNN, ABC, and NBC, and has written articles for the FINA Swimming and Diving Magazine. Today, Rowdy lives in Hawaii with his wife Judy and their three children. He manages a health and fitness center, coaches swimming and continues to feel at home in the water swimming in a Masters program.

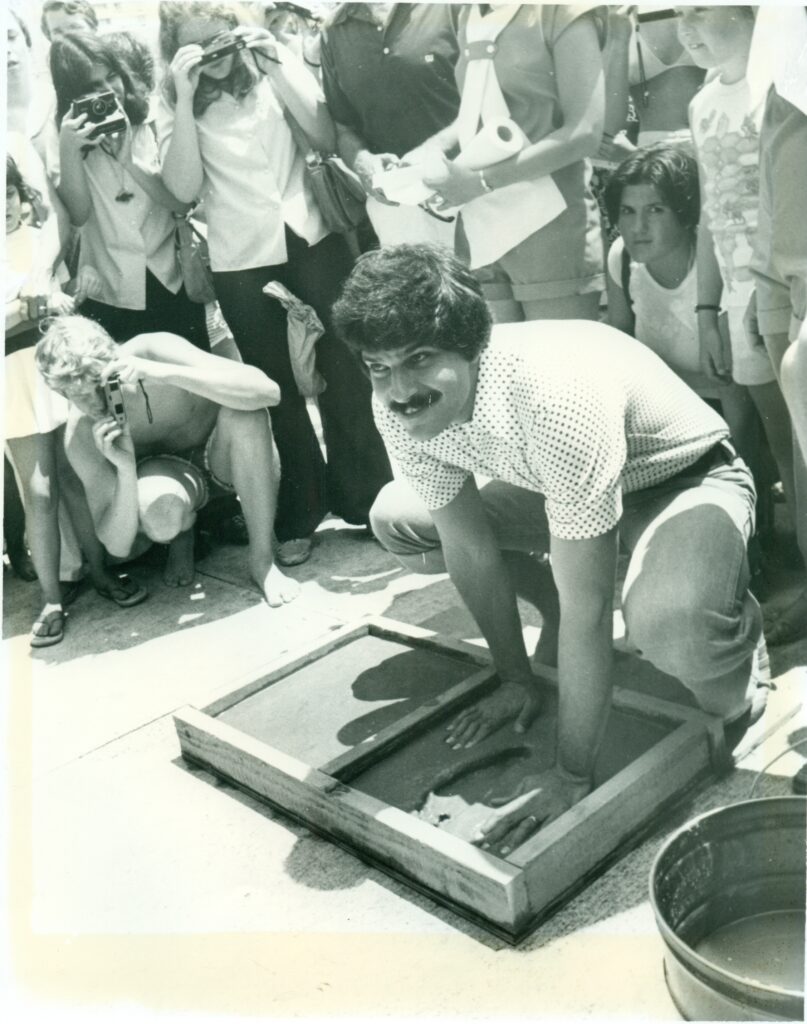

Happy Birthday Mark Spitz!!!

MARK SPITZ (USA) 1977 Honor Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: OLYMPIC GAMES: 1968 gold (4x100m, 4x200m freestyle relay), silver (100m butterfly), bronze (100m freestyle); 1972 gold (100m, 200m freestyle; 100m, 200m butterfly; 4x100m, 4x200m freestyle relay; 4x100m medley relay); PAN AMERICAN GAMES: 1967 (5 gold); WORLD RECORDS: 33; NATIONAL AAU CHAMPIONSHIPS: 24; AMERICAN RECORDS: 38; NCAA Titles: 8; 1972 “World Swimmer of the Year”.

Mark Spitz was the 1971 Sullivan Award winner as the AAU’s top athlete in any sport, an omen of things to come. His 7 gold medals in the 1972 Olympics are all the more remarkable in that all were World Records. They were in such varied distances as the sprint 100m Freestyle and the endurance 200m Butterfly. He was everybody’s World Athlete of the Year for 1972 and along with Johnny Weissmuller is rated one of the greatest swimmers the world has ever known. This remarkable consistency was not easily come by. Always brilliant he ranged from the World’s best 10-and-under to the most disappointing swimmer at the 1968 Olympics before sticking it to his critics once and for all in Munich. Spitz was fortunate to have three of the greatest swim coaches the United States has known — Hall of Famers Sherm Chavoor, Doc Counsilman and George Haines.

Sid Cassidy Named 2025 Benjamin Franklin Award Winner by CSCAA

by Matthew De George – Senior Writer

07 February 2025, 08:32am

Sid Cassidy, a long-serving official and advocate for open water swimming, was named the 2025 recipient of the Benjamin Franklin Award by the College Swimming Coaches Association of America on Thursday.

Cassidy has spent the last 20 years at Saint Andrew’s School in Florida, currently serving as its aquatics director and head coach. He has been influential in the international spread of open water swimming, advocating for its inclusion at the Olympics starting at the 2008 Beijing Games, and served as the director of that meet. He’s been part of the operation of a number of major international meets since, including the Paris Olympics.

Cassidy began serving as a coach and administrator for open water swimming with USA Swimming in 1982. He joined FINA’s technical committee for the open water discipline in 1996, becoming chairman in 2006. He held that position for World Aquatics at the 2024 Paris Olympics. In four decades of work, he has served as a national team coach for the U.S., a USA Swimming Administrator, a Swimming Safety Task Force member and been an Olympic official (including a starter for the marathon swim), race announcer and race director.

Cassidy swam at NC State, an All-American and eight-time ACC individual champion. He pursued marathon swimming professionally, swimming and coaching athletes who achieved a number of feats, including a record double crossing of the English Channel in 1991.

He coached in college, at James Madison and the University of Miami. In the high school realm, he’s been recognized as the Florida High School Coach of the Year on five occasions. He also co-owns Saint Andrew’s Aquatics and the Florida Swim School, mentoring swimmers in the pool and in open water competition. His many accolades include enshrinement in the ISCA Hall of Fame in 2024 and winning the Irving Davids/Captain Roger W. Wheeler Memorial Award from the International Swimming Hall of Fame in both 2005 and 2020, as well as the organization’s Paragon Award in 2014.

The Benjamin Franklin Award recognizes “pioneering individuals or organizations whose efforts and innovations best promote the integrity and enhancement of the student-athlete ideal.” Previous winners can be found here. It will be given at CSCAA’s Annual Meetings and Awards Celebration in Raleigh, N.C., May 4-6.

Sid Cassidy is a long time friend and supporter of ISHOF and is the Chairman of the ISHOF Selection Committee, Open Water Swimming Committee.

ISHOF Seeking Nominations for the 2025 ISHOF Aquatic Awards presented by AquaCal (formerly Paragon Awards)

ISHOF seeks nominations for the 2025 ISHOF Aquatic Awards presented by AquaCal

The International Swimming Hall of Fame announces the call for nominations for the 2025 ISHOF Aquatic Awards to be presented at the International Swimming Hall of Fame’s Masters Induction (MISHOF) and ISHOF Specialty Awards weekend, which will be held in September in Fort Lauderdale. Sponsored by AquaCal, the awards are presented each year for outstanding contributions and leadership in several swimming and aquatic-related categories.

Candidates may be nominated for the Paragon Awards in the following categories:

Competitive Swimming

Competitive Diving

Competitive Synchronized Swimming

Competitive Water Polo

Aquatic Safety

Recreational Swimming

Kindly submit your nominees by March 1, 2025. Please include any relevant data to support your nomination, the aquatic category for nomination, as well as a brief biography of each individual, a high-resolution image and their current contact information.

Get more information about the event and see the 2024 winners: https://ishof.org/announcing-the-2024-ishof-aquatic-awards-by-aquacal/

Nominations may be sent to:

Meg Keller-Marrvin

International Swimming Hall of Fame

e-mail: meg@ishof.org

(570) 594.4367

Please do not hesitate to contact us if you have any questions.

ISHOF Honors Black History Month with 2012 Gold Medallion Recipient: Superstar Milton Gray Campbell ~ Read his story!

Story by ISHOF Curator, Bruce Wigo

In 2016, Richard “Sonny” Tanabe, the legendary Hawaiian spear fisherman, author, member of the 1956 U.S. Olympic swimming team and Indiana University great stopped by the Hall of Fame with his wife Vicki and took a tour of the museum. “I always wondered why there weren’t more black swimmers,” Sonny told me, after reviewing our Black swimming history exhibit. “But I knew an African-American who was an All-American swimmer back in 1951.”

That swimmer was Milton Campbell. In 1953, as an eighteen year old, Milt was named by Sport Magazine as the best H.S. athlete in the world and it’s hard to imagine any high schooler on the planet who has ever had a superior claim to that title. As a junior, not only had Campbell won the silver medal in the decathlon at the 1952 Olympic Games, but he had also finished fifth in the open high hurdles at the U.S. trials. He scored 180 points for his high school’s football team in one season and subbing once for a sick heavyweight wrestler, he took only a minute and a half to pin the boy who would go on to be state champion. On top of that, he was an All-America swimmer. After high school, Campbell went on to star in both football and track at Indiana University, won a few national titles in the high hurdles and capped his amateur career by winning the gold medal in the decathlon at the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Australia.

Sonny Tanabe learned about Milt’s swimming skills in the fall of 1953 when both were freshmen at Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. One day, when Sonny was swimming some laps with his teammate, fellow Hawaiian and future Olympic swimmer Bill Woolsey, Milt Campbell walked into the natatorium.

“When Milt saw us he walked across the pool and jumped into the lane next to me,” recalled Sonny.“He knew Bill and me because we had some classes together and he asked if he could swim a few laps with us. ‘Sure,’ we both said. You didn’t see any black swimmers in those days, so we weren’t sure if he was joking or not. Anyway, I told him we were going to do a couple of 50’s and he said ‘OK.’ On my ‘go’ the three of us pushed off the wall and to our amazement Milt was right there with us at the 25. ‘Wow! I mean here were two future Olympic swimmers and he was matching us stroke for stroke. ‘You’re a damn good swimmer,’ I told Milt when we finished. That’s when he told us he had been an All-American swimmer in high school.”

Amazing! When I told Sonny I’d like to talk to Milt, he said he’d track him down. True to his word, he emailed me Milt’s numberand here’s the story as told to me by Milt Campbell, in his own words.

“I got interested in swimming when I was a freshman at Plainfield H.S. in New Jersey. I had just finished playing J.V. football and we had an undefeated season. My brother Tom was a junior and a three-sport star in football, basketball and track. He was the star running back for the varsity; I was the star running back for the J.V. squad. Everybody was always comparing me to Tom. While that was flattering I wantedto step out of his shadow and find my own identity. So after football season, I was determined to do something other than basketball. My plan was to see what the other sports had to offer. I had some friends on the wrestling team, so I knew what that was like, so my first stop was to check out the swim team. I knew how to swim because when I was young my dad would take our family out to a canal. He’d swim across, back and forth while my brother and I played in the shallow water. I remember my dad taking us once to the community pool. There weren’t any laws preventing us from being there, like in the south, but it was clear we weren’t welcome. That’s why we went swimming with other black folks in the canals and rivers. Anyway, it wasn’t until I was a little older and went to summer camp that I learned to swim. I learned from watching the older boys and when I tried to imitate them, they would encourage me by moving their arms and yelling, ‘Stroke your arms! Stroke your arms!’ I was a good copycat and that’s how I learned to swim. So, there I was sitting in the stands when one of the swimmers, a white boy, comes up to me and asks me what I’m doing in the pool. ‘I’m thinking about joining the swim team,’ I replied.

‘We’ve never had a colored boy swim for us,’ he said. ‘I don’t think you can swim.’ I asked him why he thought that. He said, ‘because all the waters in Africa are infested with crocodiles so your people never took to the water.’ I looked athim and said, ‘what the hell does that have to do with me? I was born in Plainfield.’ I’m not African, I thought to myself. There aren’t any crocodiles in the waters of New Jersey. What did hemean, ‘your people?’ My father knew how to swim and so did I. Whenever someone has told me I can’t do something, it has become my mission in life to prove them wrong. That has always been my strongest motivation. It’s a concept I now lecture on: It’s not important what you say to me, it’s important what I say to me.

Anyway, as the boy walked away and these thoughts were racingthrough my mind, the coach walked over to where I was sitting. Coach Victor Liske was, at 40 years of age, in the prime of his Hall of Fame coaching career that ended in 1966 with a record of 266 wins, 84 losses, 2 ties and 5 undefeated seasons. As a kid he had lost a couple of fingers and most of his left leg in a train wreck. He walked with a noticeable limp because of his prosthesis. But that didn’t hold him back. He played baseball and was a record setting backstroker in high school and was captain of Lafayette College’s swim team for the 1932-33 season.

What brought me into the pool? he asked. I told him I was thinking about joining the swim team.

‘That’s great!’ he said. ‘You’ve got big hands, big feet – you’re a great athlete – you’ll make a great swimmer!’ And I could tell hemeant it. ‘What event do you think you’d like to swim?’ he asked.

Well, I’d never seen a meet so I was kind of at a loss for words. Then it hit me. ‘You know that boy I was just talking with?” Coach nodded. ‘What does he swim?’ ‘Sprint freestyle. He’s our top sprinter.’ ‘Sprint freestyle! That’s what I want to do,’ I said. Now when I say I knewhow to swim, I did know how, but not very well. I swam with my head out and knew nothing about racing techniques, or starts and turns. But Coach Liske saw my potential and worked with me. I remember he had me do a lot of drills with a board. Progress was slow at first, but he was a good, patient teacher and I was a quick learner.

Our pool at Plainfield was shallow at one end and deep at the other. Sometimes after practice coach would bring out a ball and we’d play water polo. I was pretty big in comparison to the other boys, even as a freshman, and was pretty much unstoppable in the shallow end. Everyone would jump on me; sometimes even my own teammates would jump on me and try to pry the ball out of my grasp. It was really great fun. Finally they figured out the only way to get the ball out of my hands was to drag me to the deep end and hold me under water. I was afraid and panicked when I got dunked and didn’t have my feet on the bottom, so I’d let go of the ball. This goes back to an incident when I little. A kid jumped on my back in a canal and I almost drowned. Coach saw the panic on my face and a few days later told me stay after practice.

Coach Liske was totally unselfconscious about taking off and putting on his prosthetic legs. While I waited, Coach got changed and put on his peg leg and joined me at the edge of the deep end. ‘Get in,’ he said, jumping in after me. When we got out into the middle of the pool he told me to dunk him. ‘Go ahead, dunk me!’ So I dunked him! ‘No, really, tackle and dunk me like we’re in a water polo game.’ So I tackled him, held him under and then shoved him to the bottom of the pool. When he came up twenty feet away from me, he explained that when I dunked him he just held his breath, relaxed and went down to the bottom. Then he pushed off and returned to the surface. ‘Don’t fight, they’re going to sink you,’ he said. ‘Find another solution to the problem.’ It was his way of teaching me about life through sports. Funny thing, after I learned to be comfortable when tackled in the deep water, the team stopped asking to play polo.

At the end of my first year swimming I was second to that boy who didn’t think I’d make the team. But the next year I broke all his records. Our team went undefeated and I swam the anchor leg on Plainfield’s All-American medley relay that won the Eastern Championship. I didn’t swim my junior year because I was preparing for the Olympics trials and my senior year I was focused on getting a scholarship for football and track, so there was no time to swim again.

Sounds like you had a great experience with Coach Liske. Can you tell me more about him?

He was like a guardian angel to me. A fantastic man and I loved him dearly. I felt pretty much the same way about my track coach, Harold Brugiere. I was really blessed by having these two mentors. It’s funny I would feel that way, because I remember when I was young my dad told us to be careful around white men – that we shouldn’t trust them.

I never heard Mr. Liske berate or speak badly of anyone, but if you messed up, he made sure you learned a lesson. Here’s one example of what I’m talking about. I had a lot of friends on the wrestling team and after swim practice I would wander into the wrestling room and fool around, wrestle with the guys. One day, the wrestling team had a match against Jefferson High. It was a big match. I wanted to see it so bad that I told Mr. Liske I was sick and couldn’t swim that day. He said ‘OK, go home and get some rest and I’ll see you tomorrow.’ Instead of going home, I went up through a back stairwell and entered a back door to the gymnasium so I could watch the match. I was near the locker room and when the door opened I could see our heavyweight throwing up. When coach Rosy came out I asked him what was the matter. ‘Oh, he’s just nervous. He’ll get over it,’ he said. ‘Well, if he doesn’t get over it and you need me, I’ll do it,’ I told him. ‘Thanks Milt, but you’d get hurt. This Jefferson guy’s a killer. One of the best in the state.’ Well, as it looked like the match was going to down to the last weight class, the coaches were talking about forfeiting the heavyweight class because guy’s problem was more than nerves,he was really sick. So the assistant coach starts in on coach Rosy. “Milt’s strong as an ox and I’ve seen him wrestle with the boys after our practice. What have we got to lose?’ Finally, Rosy relented, ‘Ok, get him dressed.” Well, I pinned the guy in one minute and 28 seconds and Plainfield won the match. That guy went on to win the state title by the way. When I got to school the next day, I was a hero. Everybody was congratulating me in the hallways on the way to my first class – which was math with Mr. Liske. Unlike everyone else in the school, Mr. Liske wasn’t happy to see me. As we took our seats and got out our books, he sternly said: ‘put your books away! It has come to my attention that we have a liar in our midst.’ He then proceeded to lecture us on the virtue of honesty in a way that I felt obligated to apologize to him before the whole class. I never felt so bad. Here was a guy who had been so good to me and I lied to him. When the bell rang to dismiss the class, I couldn’t wait to get out of that room, but Mr. Liske called me over. Oh No! Not more, I thought. But instead of being mad, he patted me on the back and said, “great job!” I was forgiven andat swim practice that afternoon all was well again!

I stayed in contact with Coach Liske over the years and when he was in failing health in 2008 I visited him often and he would cry every time he’d see me. I told him if he kept crying I wasn’t go- ing to visit him any more. ‘You don’t need to cry when you see me,’ I said. ‘Think about the good times we had.’ ‘That’s why I’m crying,” he said. On one of my last visits before he passed away at the age of 98, we had a good laugh over the time we beat the Army Plebes 40 -35, by winning the last relay on which I was the anchor and came from behind to win the race. We sang on the bus all the way home, from the time we left West Point to the time we pulled into the high school parking lot. It was one of those days you, your team and your coach never forget.

We talked a little about why more African Americans aren’t swimming and Milt understands the problem. It’s all in the mind. We have to change people’s mental attitude. I had the example of my father who was a good swimmer and then I had coaches who helped me to believe anything was possible.

As the greatest athlete of his generation, I wondered why Milt didn’t receive the same commercial success and public recognition as otherGold Medal decathletes that went before or after him. Milt wasn’t movie star handsome like Bob Mathias or Rafer Johnson, but I believe, like many social historians, that it was because America wasn’t ready for black man to have the title of the World’s Greatest Athlete. Add that to the fact that he married a white woman at a time when half of the states had anti-miscegenation laws and you can see why Milton Campbell is aforgotten hero.

I can only imagine what kind of swimmer or water polo player Milt Campbell might have been, or the impact he might have made on our culture and the widely accepted stereotype that “blacks can’t swim” had he continued swimming. Listening to Sonny Tanabe and Milt tell their stories, and reading what coach Liske told people for over fifty years, I’m convinced that if Milt stuck with swimming he could have been an Olympic Champion in our sport too!