A Week of Katie Ledecky Stats (Day Four): Distance Ace Has Made Sub-4:00 Her Home in 400 Freestyle

by John Lohn – Editor-in-Chief

14 May 2025,

A Week of Katie Ledecky Stats (Day Four): Distance Ace Has Made Sub-4:00 Her Home in 400 Freestyle

In recognition of Katie Ledecky lowering her world record in the 800-meter freestyle to 8:04.12, Swimming World continues its Week of Katie Ledecky Statistics. Each day for a week, we are running a short piece that highlights Ledecky-related stats, numbers that place additional context on her legendary career.

There’s no debate that the 800-meter freestyle and 1500 freestyle are recognized as Katie Ledecky’s premier events, with the 400 freestyle solidly slotted in the No. 3 position. Since capturing Olympic gold in the 400 freestyle at the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, Ledecky has been eclipsed in the discipline by Ariarne Titmus. The Australian ace has won the past two Olympic titles, with Ledecky earning silver and bronze in Tokyo and Paris.

Yet, Ledecky remains the most-decorated female in terms of sub-4:00 performances, a time that has been cracked by only five women in history – Federica Pellegrini, Ledecky, Titmus, Summer McIntosh and Erika Fairweather. Of the 56 all-time marks under four minutes, 31 belong to Ledecky. That total accounts for 55.35% of the historical sub-4:00 efforts. Next on the list is Titmus with 13 trips under four minutes, followed by McIntosh with nine.

Ledecky’s personal best in the 400 freestyle sits at 3:56.46, her winning time in the Olympic final in Rio. Earlier this month, she clocked the second-fastest time of her career, a 3:56.81 showing at the TYR Pro Series in Fort Lauderdale. Ledecky has been sub-4:00 at least once in 13 consecutive years, a streak that began in 2013.

Great Races: When Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner Broke a Special Barrier – A Unique Summer Pursuit Of Sub-50

by John Lohn – Editor-in-Chief

26 April 2025

When Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner Chased Sub-50: A Unique Summer Pursuit

Swimming World’s Great Races Series has featured numerous duels between star athletes. In this edition, Jim Montgomery and Jonty Skinner engaged in a great race, albeit one in separate pools.

The most iconic barrier-breaking performance in sports history is not difficult to decipher. It is the 3:59.4 mile run by Great Britain’s Roger Bannister in 1954, marking the first time the four-minute threshold was eclipsed. The effort captured the attention of the world and opened the imagination of what was possible in an athletic endeavor.

Fourteen years later, American sprinter Jim Hines produced another legendary outing, as he became the first man to officially cover the 100-meter dash in under 10 seconds. The speed Hines displayed in 1968 handed him the gold medal in the event at the Olympic Games in Mexico City.

From the equine world, Secretariat is celebrated as the greatest racehorse of all-time and used the 1973 Kentucky Derby to put on a show that remains unmatched. Running 1:59.40 at Churchill Downs, Big Red – as he was known – became the first horse to crack the two-minute barrier in the Derby, which is run on a 11⁄4-mile track. His Triple Crown was completed several weeks later, when he delivered his epic run at the Belmont Stakes

In the pool, breaching the 50-second barrier in the 100-meter freestyle became a major storyline of 1976. The men at the center of the chase, American Jim Montgomery and South African Jonty Skinner, never met during that Summer of Speed, as politics kept them apart. Nonetheless, they engaged in an entertaining, albeit long-distance, duel.

The 100 freestyle has long been considered swimming’s blue-ribbon event, and the territory of some of the sport’s legends. Duke Kahanamoku, Johnny Weissmuller, Don Schollander and Mark Spitz, to name a quartet, won Olympic gold in the two-lap discipline. More, Weissmuller was the first man to break the one-minute barrier, accomplishing the feat in 1922. Over the next half-century, the record continued to dip, to the point where sub-50 became a legitimate possibility midway through the 1970s.

In most eras, the Olympics bring together the best competitors an event has to offer. However, that was not the case at the 1976 Games in Montreal, where a key figure was missing from the pool deck. Four years before President Jimmy Carter infused politics into sports by leading a United States boycott of the 1980 Olympics in Moscow, politics played a role in the 1976 Games.

Due to its apartheid policies, South Africa was banned from the Olympic Games by the International Olympic Committee in 1964, a restriction that lasted until the 1992 Games. Caught in the middle of his country’s segregation practices, which he did not support, was Skinner, one of the world’s premier sprint freestylers.

Competing collegiately for the University of Alabama, Skinner established himself as an NCAA and United States national champion in the 100 freestyle. As much as Skinner might have been detached from his homeland and apartheid, his citizenship – based on IOC rule – made Skinner ineligible to compete on the biggest stage in sports. It was a hand Skinner was forced to accept, and it also dealt a blow to the depth of the 1976 Games. Without Skinner, Montgomery raced the clock, and not a rival who would have raised the level of competition.

As he prepared for the Montreal Games, Montgomery was a well-known commodity. In 1973, Montgomery flourished as a member of Team USA at the inaugural World Championships. In Belgrade, Yugoslavia, Montgomery earned gold medals in the 100 freestyle and 200 freestyle, and helped the United States win three relay titles.

Following the World Champs, Montgomery joined the power program of Indiana University, which was guided by Hall of Fame coach Doc Counsilman. As a Hoosier, Montgomery captured three individual NCAA titles and developed into an Olympian, thanks to Counsilman’s influence. Although Montgomery exhibited natural ability before working with Counsilman, the coach enabled Montgomery to hone his mental approach.

Jim Montgomery

Ahead of the Olympics in Montreal, Counsilman convinced the men’s team that it could establish itself as the greatest team in history. Indeed, that is what Team USA accomplished, as it won 12 of the 13 events and swept the podium in four disciplines.

“He’s the smartest guy I’ve ever known in my entire life,” Montgomery said of Counsilman. “Just sheer brain power. And he had a sense of humor. He just put it right on the plate. ‘We’re going to absolutely dominate. That’s my goal, and that’s my goal for you guys.’”

Montgomery personally accepted Counsilman’s challenge.

Coming off a bronze medal in the 100 freestyle from the 1975 World Championships, Montgomery elevated his performances in Montreal, a fact that was evident during the semifinals of the 100 freestyle. Erasing any doubt over who was the favorite for gold, Montgomery blistered a world record of 50.39, a mark which was nearly more than a second faster than the No. 2 seed, Italian Marcello Guarducci (51.35). Montgomery’s dominance allowed he and Counsilman to experiment in the final.

“After the prelims, we figured we had the race pretty much won,” Counsilman said. “So we risked it. We swam the race to break the record by going out harder. We figured that even if he died a little coming home, he’d still have enough to win.”

Montgomery and Counsilman were not just concerned with lowering the world record. The final was about taking Montgomery into – pardon the pun – uncharted waters. A sub-50 performance was within reach and producing a readout on the clock that started with a “4” was an enticing opportunity.

As a member of a squad that was obliterating the opposition, there was a competition within a competition of sorts for Team USA. Who could produce the most memorable performance? For that honor, the battle primarily came down to Montgomery and John Naber, the University of Southern California star who won the 100 backstroke and 200 backstroke events in world-record time. Montgomery, though, had the extra power of delivering a barrier-breaking outing.

The bronze medal Montgomery claimed in the 100 freestyle at the 1975 World Champs also served as motivation. During 1974 training, Montgomery and Counsilman toyed with a workload that was more geared toward the middle-distance events. Ultimately, it cost Montgomery some of his pop in his main event, but the error was better realized at the World Champs, rather than the Olympics. By the time Montreal called, Montgomery was in peak form and possessed lofty target times.

“I thought realistically I could swim 49.4 or 49.5,” Montgomery said. “I had some relay splits that were that fast at that time, and back then we didn’t have the fancy relay starts they do now. If I didn’t have that training failure in 1974, I wouldn’t have become Olympic champion. I was stronger and handled the power training necessary for the 100 free.”

The confidence brewed by Counsilman in Montgomery was clear from the start in the final as the 21-year-old bolted to the front of the field and held a half-body-length lead at the turn. Coming off the wall in 24.14, the question wasn’t whether Montgomery would win the race, but if he could join Bannister and Hines as a barrier breaker. Indeed, Montgomery was given access to the club by the slimmest of margins, the scoreboard flashing 49.99. Countryman Jack Babashoff followed in the silver-medal position, well behind in 50.81.

“This will put Montgomery in the Swimming Hall of Fame,” Counsilman said. “I think this is the last barrier in swimming. We broke one minute in the 100 freestyle 50 years ago, and I don’t think we are going to break 40 seconds. So this is it, at least for a long time. I thought it was the best swim of the Olympics, and we’ve had some good swims.”

Counsilman was prophetic in his statement, as Montgomery was enshrined into the International Swimming Hall of Fame as a member of the Class of 1986. While Montgomery’s profile obviously highlights his gold medal, it also references his barrier-breaking identity and place in history alongside Bannister.

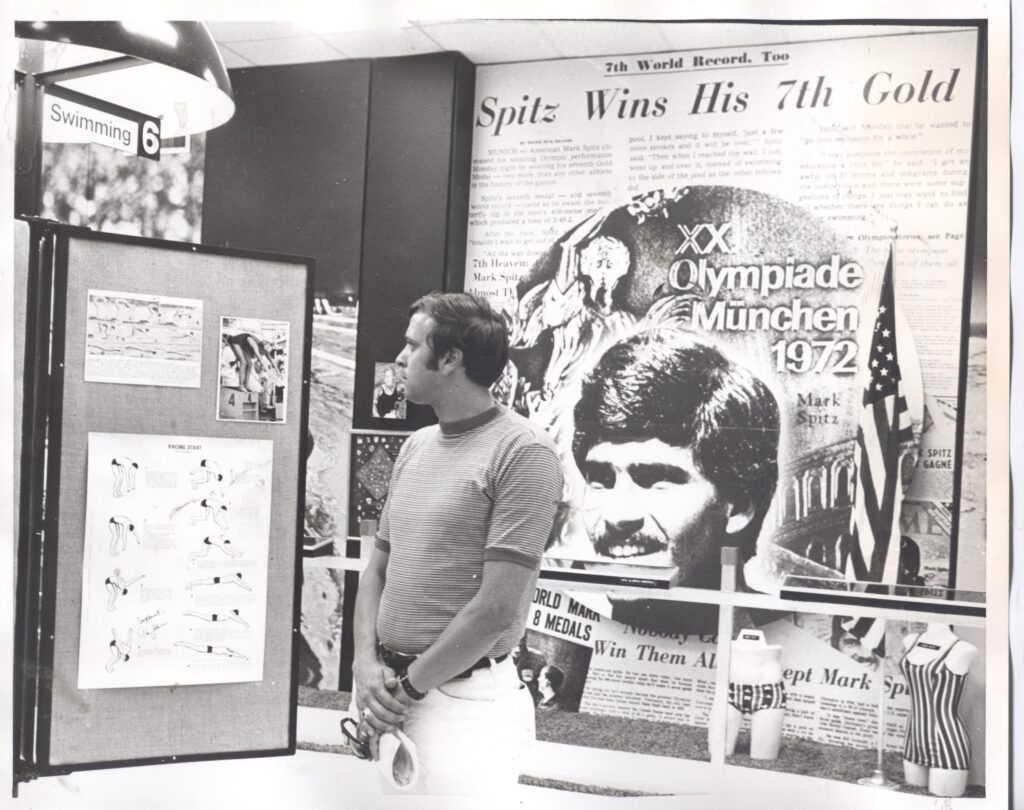

Jonty Skinner – Photo Courtesy: Amelia B. Barton

As monumental as it was, Montgomery’s world record and solo status in the sub-50 club was short lived. Without the opportunity to race at the Olympics, Skinner identified the Amateur Athletic Union National Championships in Philadelphia as his focus meet for the summer. Scheduled for three weeks after the Olympics, the competition lacked the firepower present in Montreal, but Skinner wasn’t really racing the men in the adjacent lanes in Kelly Pool. Instead, Skinner was racing the clock and Montgomery.

Before settling on Philadelphia as the stage for his personal Olympics, an attempt was made to get Skinner American citizenship in time to compete at the United States Olympic Trials. A petition with more than 50,000 signatures was sent to Washington, D.C. and Representative Walter Flowers, a democrat from Alabama, introduced a bill to Congress – HR 12257 – that would award Skinner citizenship in time to compete at Trials. Alas, the push on Skinner’s behalf fell through, leaving him as a spectator to the Montreal Games.

“I really had no issues with not being there since I was focused on Philly,” Skinner said. “It ticked me off that (Montgomery) 50, and that is what fueled me the last few weeks getting ready. I had focused on breaking 50 as a season goal, so when (Montgomery) went 49.9, I adjusted to 49.8. I wasn’t nervous at all. I did a lot of visualization to prepare, so I was ready in my mind.”

Racing alone or without rivals to push the pace is not an easy chore, but Skinner had plenty of motivation. Despite besting the field by more than two seconds, Skinner relented. He went out in 23.83, .31 quicker than the split of Montgomery, and he came home slightly quicker as well. At the touch, Skinner produced a time of 49.44 to shave .55 off Montgomery’s performance from the Olympic Games.

Although an Olympic medal was not draped around Skinner’s neck, the moment was as meaningful. He had an opportunity taken from him for no fault of his own, but Skinner turned his situation into a positive. His world record was so impressive, it last nearly five years, until Rowdy Gaines clocked 49.36 in April 1981. As impressive, Skinner’s time would have won Olympic gold in 1980 and 1984 and would have earned the bronze medal at the 1988 and 1992 Games.

“Coach, I did it,” said Skinner to his coach at the University of Alabama, Don Gambril. “Since I couldn’t swim against (Montgomery), my opponent had to be the clock. I just kept telling myself, ‘This is your only chance. Don’t blow it.’”

Linked by the Summer of 1976, Montgomery and Skinner have remained involved in the sport in prominent ways. Montgomery followed his Olympiad by winning the silver medal in the 100 freestyle at the 1978 World Championships and, following a brief retirement, started training for the 1980 Olympic Trials, a pursuit that ended when the American boycott of the Moscow Games was announced. Montgomery eventually shifted into Masters competition and has operated swim clubs and swim schools.

As for Skinner, who was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1985, he took his skills in the water to the deck and a coaching career. Skinner served as the first coach of USA Swimming’s Resident National Team at the United States Olympic Training Center and later held the role of USA Swimming’s Director of Performance Science and Technology. The latter role is one he also held for British Swimming. Before retiring in 2020, Skinner returned to the college ranks, serving as an assistant coach for the University of Alabama, and then Indiana University.

“I could always talk from experience when it came to helping swimmers prepare for peak-level events,” Skinner said of the transition from elite athlete to coach. “I very rarely talked about (his world record in Philadelphia), but the athletes knew my background, so they trusted my opinions.”

Montgomery and Skinner each had his moment to shine, and history looks back favorably at each career. Montgomery will always have his Olympic gold medal. Skinner will always have his day, Aug. 14, 1976, as proof of overcoming disappointment and factors beyond one’s control. There is room to honor both men.

“The Olympics were one day, and this was another,” Skinner said. “But I hope Jim was watching me on TV.”

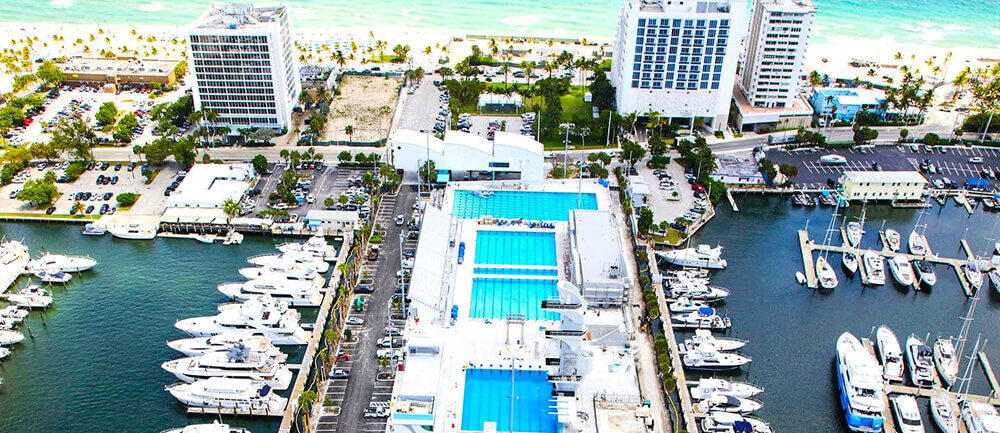

Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex Once Again a World-Record Centerpiece (A List of the Records)

by John Lohn – Editor-in-Chief

04 May 2025

Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex Once Again a World-Record Centerpiece

The Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex, originally built in 1965, has been no stranger to world records through the years. Some of the biggest names in the sport have competed at the venue since its unveiling, including numerous members of the International Swimming Hall of Fame. Simply, Fort Lauderdale is a destination for elite athletes in the sport, and that fact was on display over the past four days.

The USA Swimming TYR Pro Series was held from Wednesday through Saturday at the renovated facility, with sensational performances highlighting each day of action. Notably, Fort Lauderdale returned to world-record status when Katie Ledecky lowered her global standard in the 800 freestyle to 8:04.12 and Gretchen Walsh twice set world records in the 100 butterfly, first going 55.09, and then 54.60.

Thanks to the efforts of Ledecky and Walsh, the Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex now boasts 13 world-record swims in its history. The first record was set by Catie Ball in the 100-meter breaststroke in 1966, with the last before this weekend set by Michael Phelps in the 400 individual medley in 2002. The latter race featured Phelps and Erik Vendt both going under the previous world record.

Here is a look at the 13 world records set at the Fort Lauderdale Aquatic Complex

Catie Ball (100 Breaststroke: 1:15.60) – 1966Pam Kruse (400 Freestyle: 4:36.80) – 1967Andy Coan (100 Freestyle: 51.11) – 1975Mary T. Meagher (200 Butterfly: 2:08.41) – 1979Mary T. Meagher (200 Butterfly: 2:07.01) – 1979Kim Linehan (1500 Freestyle: 16:04.49) – 1979Martin Zubero (200 Backstroke: 1:57.30) – 1991Mike Barrowman (200 Breaststroke: 2:10.60) – 1991Natalie Coughlin (100 Backstroke: 59.58) – 2002Michael Phelps (400 Individual Medley: 4:11.09) – 2002Gretchen Walsh (100 Butterfly: 55.09) – 2025Katie Ledecky (800 Freestyle: 8:04.12) – 2025Gretchen Walsh (100 Butterfly: 54.60) – 2025

May Featured Honoree: Dorothy Poynton (USA) and her Memorabilia

Each month ISHOF will feature an Honoree and some of their aquatic memorabilia, that they have so graciously either given or loaned to us. Since we are closed, and everything is in storage, we wanted to still be able to highlight some of the amazing artifacts that ISHOF has and to be able to share these items with you.

We continue in the new year, April 2025, with 1968 ISHOF Honoree, Dorothy Poynton Honor Diver. Dorothy Poynton donated many fabulous things to ISHOF and we want to share some of them with you now. Also below is his ISHOF Honoree bio that was written the year he was inducted.

Commemorative Medal awarded to Dorothy Poynton from Mayor LaGuardia for 3m Springboard Diving

1932 Participant medal, 1936 Participant medal, 1936 Gold 10m platform, 1936 Bronze, 1932 Gold 10m p

1 Holborow Swimming Club Medal given to Dorothy Poynton from her Coach Frank Holborow

Ryan Lochte to be inducted into ISHOF as Honor Swimmer in Singapore as part of Class of 2025

photo courtesy: World Aquatics

by: John Lohn

From the moment Ryan Lochte made his Olympic debut for the United States at the 2004 Games in Athens, he became a critical cog of American success on the international stage. As a four-time Olympian (2004-2016), Lochte obviously possessed the talent necessary to flourish at the elite level.

But the Floridian also owned another key attribute: Belief. Package those traits together and it’s no wonder that Lochte is now an inductee of the International Swimming Hall of Fame.

“I believe in myself,” Lochte said. “A lot of people look at Michael (Phelps) and think he can’t be beaten. That’s not me. I know I can beat him. That’s the competitive edge that I have. I never feel like I’m going to lose, no matter who I’m racing. I always feel like I can win.”

Lochte’s portfolio is stunning, thanks to 12 Olympic medals (six gold), 27 medals from the World Championships and 38 medals from the World Short Course Championships. He is one of the greatest collegiate swimmers in history and stood out in both the long-course and short-course pools.

While his pure talent and work ethic certainly elevated Lochte to the top of his sport, his mental toughness and belief in his abilities played equally critical roles on his road to Hall of Fame status.

Learn more about Ryan Lochte and the other 11 outstanding Honorees who will be inducted this year at ISHOF’s Diamond Anniversary in Singapore! Buy your tickets NOW for ISHOF’s 60th Anniversary of the Honoree Induction Ceremony in Singapore in conjunction with the World Aquatics World Championships

WHEN: Monday, July 28, 2025, 1:00 PM

WHERE: Park Royal Collection, Marina Bay, Singapore

Tickets are NOW ON SALE ~ purchase them HERE!

Buy your tickets NOW for ISHOF’s 60th Anniversary of the Honoree Induction Ceremony

ISHOF Class of 2025

Anthony Ervin (USA) Honor Swimmer

Ryan Lochte (USA) Honor Swimmer

Federica Pellegrini (ITA) Honor Swimmer

Joseph Schooling (SIN) Honor Swimmer

Ous Mellouli (TUN) Honor Open Water Swimmer

Chen Ruolin (CHN) Honor Diver

Endre “Bandi” Molnar (HUN) Honor Water Polo Player

Andrea Fuentes (ESP) Honor Artistic Swimmer

Gregg Troy (USA) Honor Coach

Captain Husain Al Musallam (KUW) Honor Contributor

Sachin Nag* (IND) Honor Pioneer Swimmer

Guo Jingjing (CHN) Honor Diver (Class of 2016)

*deceased

The International Swimming Hall of Fame (ISHOF) is proud to announce this truly international Class of 2025. This year, ISHOF will induct 12 honorees from nine countries. In addition, ISHOF will be inducting Honorees from four new countries that we have never had Honorees inducted from before, Kuwait, India, Tunisia, and Singapore.

Happy Birthday Enith Brigitha!!

Enith Brigitha (NED)

Honor Swimmer (2015)

FOR THE RECORD: 1972 OLYMPIC GAMES: 8th (100m freestyle), 6th (100m backstroke), 6th (200m backstroke), 5th (4x100m freestyle); 1976 OLYMPIC GAMES: bronze (100m freestyle), bronze (200m freestyle), 4th (4x100m freestyle relay), 5th (4×100 medley relay), 10th (100m backstroke); FIVE SHORT COURSE WORLD RECORDS: 2 (100m freestyle), 2 (200m freestyle), 1 (400m freestyle); 1973 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: bronze (100m freestyle); silver (200m backstroke); 1975 WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS: bronze (100m freestyle, 200m freestyle, 4x100m freestyle); 1974 EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS: bronze (100m freestyle, 100m backstroke), silver (200m freestyle, 4x100m freestyle); 1977 EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIPS: silver (100m freestyle, 4x100m freestyle).

Enith Brigitha was born on the West Indian Island of Curacao, where she first learned to swim in the Caribbean Sea. By the time she moved to Holland with her mother and brother in 1970, she had become the island’s most promising swimmer.

Two years later, swimming for Coach Willie Storm at the Club Het Y in Amsterdam, Enith qualified for the 1972 Munich Olympic Games and reached the final in four events, and this was just the start of her success. At the 1973 inaugural FINA World Championships in Belgrade, she claimed a silver medal in the 200 meter backstroke and a bronze medal in the 100 meter freestyle. At the 1974 European Championships she won five medals, including four individual medals for the 100 and 200 meter freestyle and backstroke events. In 1975, at the II FINA World Championships in Cali, Columbia, she added three bronze medals to her collection, including individual pieces of hardware in the 100 and 200 meter freestyle.

At the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal, she earned individual bronze medals in both the 100 and 200 meter freestyle, and at the 1977 European Championships, she won a silver medal in the 100 meter freestyle.

Enith was a genuine superstar in an era dominated by women swimmers from the German Democratic Republic. All told, she set five short course world records and collected 21 Dutch titles in the freestyle, backstroke, medley and butterfly events. She won the Dutch 100 meter freestyle title seven years in a row, was twice named Dutch Sportswoman of the Year – and has the distinction of being the first person of African descent to win Olympic medals in swimming.

Still, her accomplishments have for too long been diminished by the dazzling success of the East Germans. Of the 11 individual medals Enith won at the Olympic Games, World and European Championships – only East German swimmers finished ahead of her in 10 of those events, the one exception being America’s Shirley Babashoff, in the 200 meter freestyle at Munich.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Dr. Werner Franke and his wife Brigitte Berendonk, discovered files from the Stasi – the East German secret police – documenting the fact that all of the East German swimmers who finished ahead of Enith Brigitha had been systematically doped, without the knowledge or consent of them or their parents, as a matter of national policy. To the GDR’s rulers, these young athletes were nothing more than pawns in

a global chess game, sacrificial lambs on the altar of East German ideology. Had the world known this at the time, the steroid and testosterone enhanced performances of the GDR’s athletes would have resulted in their disqualification, and Enith’s record would be even more stellar than it is. She also would be recognized today as the first black Olympic champion in swimming history, beating Anthony Nesty of Suriname to the top of the podium by 12 years.

There’s more to life than just swimming, of course. After hanging up her swimsuit and retiring from the sport, Enith married and had three daughters. She moved back to Curacao, where she opened her own swimming school and taught children to swim. Once her daughters were ready to go to University, the family moved back to Holland, where they remain today. Enith says, “With the girls in Holland and with our three grandchildren, it’s not so easy to leave Holland again.”

Happy Birthday Dara Torres!!

Dara Torres (USA)

Honor Swimmer (2016)

FOR THE RECORD: 1984 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (4×100 m freestyle); 1988 OLYMPIC GAMES: silver (4×100 m medley), bronze (4×100 m freestyle); 1992 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (4×100 m freestyle); 2000 OLYMPIC GAMES: gold (4×100 m freestyle, 4×100 m medley), bronze (50 m freestyle, 100 m freestyle, 100 m butterfly); 2008 OLYMPIC GAMES: silver (50 m freestyle, 4×100 m freestyle, 4×100 m medley); 1986WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS (LC): silver (4×100 m freestyle); 1987 PAN PACIFIC CHAMPIONSHIPS: gold (100 m freestyle, 4×100 m freestyle, 4×100 m medley); 1983 PAN AMERICAN GAMES: gold (4×100 m freestyle); SIX WORLD RECORDS: three individual (50m free), three relays (4x100m free, 4x100m medley)

Dara Grace Torres grew up in Beverly Hills, California, where she learned to swim in her family’s backyard pool. At the age of seven, she followed her brothers to swim practice at the local YMCA. During her junior year of high school, Torres moved to Mission Viejo, CA, to train with Hall of Fame Coach Mark Schubert, and in 1983 she broke the world record in the 50-meter freestyle. The next year, while not yet a senior in high school, she won her first Olympic gold medal as a member of the USA’s 4×100 freestyle relay team.

Swimming for Randy Reece at the University of Florida, Torres earned 28 NCAA All-American swimming awards and at the 1988 Olympic Games, she won two silver medals swimming on relays. She finished her collegiate athletic career playing volleyball and took two years off before returning to win her second Olympic relay gold medal in Barcelona, Spain during the summer of 1992.

After 1992, Torres lived what appeared to be a glamorous life. She moved to New York City, worked in television, and as a Wilhelmina model she became the first athlete model in the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue. Then in the spring of 1999, despite not having trained in a pool for seven years, she decided to give the Olympics one more try.

Training with coach Richard Quick in Palo Alto and Santa Clara, Dara made the Olympic team for the fourth time, at the age of 33. She returned home with five medals, more than any other member of the team, including three in individual events, and retired.

In 2005, while pregnant with her first child, Dara began swimming three or four times a week at the Coral Springs Aquatic Complex, to keep fit. After giving birth to her daughter, Tessa Grace, in April 2006, she entered two Masters meets and posted times that emboldened her to try another comeback. She asked Coral Springs coach Michael Lohberg if he would coach her, and a little over a year later, she won the 100-meter freestyle at the U.S. Nationals in Indianapolis. Three days later, she broke the American record in the 50-meter freestyle for the tenth time – an amazing 24 years after setting it for the very first time. In 2008, Dara qualified for her fifth Olympic team and at the 2008 Beijing Games, she became the oldest swimmer to compete in the Olympics. Dara returned home with three silver medals, including the heartbreaking 50-meter freestyle race where she missed the gold by 1/100th of a second.

In 2009, Dara won the ESPY award for “Best Comeback,” was named one of the “Top Female Athletes of the Decade” by Sports Illustrated magazine and became a best selling author with the release of her inspirational memoir, Age is Just a Number.

Dara continued swimming after recovering from reconstructive knee surgery and with the encouragement of coach Lohberg, she set her sights on making a record sixth U.S. Olympic swim team. When she just missed making the London Olympics by nine-hundredths of a second in the 50-meter freestyle at the 2012 US Swimming Olympic Trials, she announced her retirement with a smile on her face and her six-year old daughter Tessa in her arms.

Olympian, television personality, fitness guru, Queen of the Comeback, best-selling author and mother. Dara Torres is many things to many people, but above all, she is an inspiration.

Today in Swimming History ~ April 11, 1896 ~ Swimming begins at the Athens Olympic Games ISHOF Honoree ~Alfred Hajos wins first Olympic gold medal ever awarded in swimming

Today in Swimming History…….129 years ago, on April 11, 1896, ISHOF Honor Swimmer, Alfred Hajós of Hungary beats Otto Herschmann of Austria by 0.6s to win the inaugural Olympic 100m freestyle final in a time of 1:22.2 at the first Olympiad in Athens, Greece; He would also take gold in the 1200m on the same day.

Hajos and his Hungarian teammates were one of only three countries that competed in first Olympic Games in swimming. The other two were Austria and Greece. There was a fourth country that competed in the Games, the U.S.A., but they competed in sports other than swimming.

Hajos was inducted into ISHOF in 1966. Read about the rest of his life after that first Olympiad below.

ALFRED HAJOS (HUN) 1966 HONOR SWIMMER

The information on this page was written the year of their induction.

FOR THE RECORD: OLYMPIC GAMES: 1896 gold (100m, 1200m freestyle); first Olympic swim champion. The first modern Olympic swimming champion was Alfred Hajos, a double winner at Athens in 1896. Hajos won the 100 meter freestyle in 1:22.2 beating out the local favorite Chorophas and Herschmann of Austria.

Olympic Swimmers at 1896 Athens Games

The Austrians got back in the swim as Paul Neumann won the 500 meter freestyle over two more Greeks while Hajos was resting up for his second win, the 1200 meter freestyle in 18:22.2. Thus Alfred Hajos took home two of the three gold medals offered in swimming. His teammate, Zoltan Halmay got only a third, but came back in the next four Olympics to be the other Hungarian from the first Olympics to make the International Swimming Hall of Fame. The Austrian Neumann became a prominent U.S. doctor. Hajos stayed in Hungary, survived World War I, and came back to the Olympics 28 years after his first try, this time 1924 Paris, where he won another gold medal. It was in a cultural Olympic art and architectural contest.

Architect Hajos later designed Budapest’s finest competitive swimming pool, club and baths in which Hungary trained its next great Olympic 100 meter champion, Czik Ference in 1936, and its great postwar women swimmers, Szoke, Gyenge, Szekely, Temes and the Novak Sisters.

The Hajós Alfréd National Swimming Pool in 1931… (Photo: Fortepan/No.: 58265)

The National Swimming Pool was opened in 1930. A contemporary newspaper called it the crown of Alfred Hajós’ career.

The National Swimming Pool was commissioned by the Royal Hungarian Ministry for Religion and Education. The minister, Kuno Klebersberg (1875–1932), saw the swimming pool as a vital project.

Happy Birthday Ted Stickles !!!

EDWARD “TED” STICKLES (USA) 1995 Honor Swimmer

FOR THE RECORD: 4 WORLD RECORDS: 400m individual medley; 8 U.S. NATIONAL AAU CHAMPIONSHIPS: 200m individual medley, 400m individual medley.

Ted Stickles swam with Doc Councilman’s legendary Indiana University swim team from 1962-1965. At on point during his career, he and his roommate, Hall of Famer Chet Jastremski, held a total of seven world records. Ted dominated the individual medley throughout the early ’60s, breaking a total of nine world records throughout his career.

His mother taught him to swim at an early age, but it was not until he entered high school that Ted began competitive swimming. After enjoying a successful high school career, Hall of Famer Doc Councilman recruited him to his IU team.

At first, Ted felt that Doc had made a mistake in his recruitment, but before long, he surprised himself and began to break unforgettable records. Ted was one of the first people to actually train for the individual medley events. Ted’s ease in moving from one stroke to another and fluidity without breaking stroke helped him be the first person to break two minutes in the 200 yard individual medley and five minutes in the 400 meter individual medley. For a span of three years, Ted Stickles held all of the world records in the individual medley events.

At the height of his career, he developed tendonitis in his elbow, hindering his ability to train. Yet Ted continued to swim and barely missed making the ’64 Olympic team. This was a disappointment because his sister, Terri Stickles, made the team; they would have been the first brother and sister to make an Olympic team.

Ted went on to coach swimming for the University of Illinois and Louisiana State University. Presently, he resides in Louisiana with his wife and two children and is event management director for all athletic functions at Louisiana State University.

Happy Birthday Tom Stock!!

Tom Stock (USA)

Honor Swimmer (1989)

The information on this page was written the year of their induction.

FOR THE RECORD: WORLD RECORDS: 10 (100m, 200m, 220yd backstroke; relays); AAU NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS: 11 (100m, 200m, 220yd backstroke; relays; AMERICAN RECORDS: 14 (200yd, 220 yd, 100m, 200m backstroke; relays).

Tom Stock may just be the greatest backstroker who never swam in the Olympics, due to prolonged illness before the 1964 Olympic Games. He may have been the smallest backstroker to hold a world record. He weighed in at 130 lbs. and set 10 world records. When he was in his second month of competition at Indiana University, Stock became the first man in history to swim the 200 yard backstroke under 2 minutes. This was a performance that caused his coach, “Doc” Counsilman to put a sign on the locker room door which said, “It’s not the size of the dog in the fight, but the size of the fight in the dog.”

This desire and an amazing feel of the water, long arms and a powerful kick, made Tom Stock great in the opinion of his famous coach. To the spectators he looked like he was riding on top of the water from the waist up. This unique buoyancy, plus the fastest arm turnover yet seen in backstroke, took him to 11 National championships, 14 American records and five world records in the 100 meter, 200 meter, 110 yard, 220 yard backstroke and the 400 meter medley relay. For four years he was the World Record holder and “King” of the 200 meter backstroke.

It started just after the Rome Olympics and finished just before Tokyo in 1964. In between, he victoriously represented the USA in Japan, South America, and Europe and was The American Swimmer of the Year in 1962. Stock had only two coaches, Dave Stacy at Bloomington, Illinois and “Doc” Counsilman at Bloomington, Indiana. He missed making the 1960 U.S. Olympic team by a judge’s decision. They took only two and not three as chosen in previous Olympics.